Many patients require at least one peripheral intravenous cannula (also known as an intravenous catheter) (PIVC) during their hospital stay in order to receive IV fluids and medications, blood products or nutrition (ACSQHC 2021).

PIVC complications are common, but they can be prevented or minimised by routine assessment. This article discusses the key points of PIVC assessment.

Is an IV Cannula Needed?

Does the patient need this PIVC?

In Australia, around 43% of PIVCs are left in without orders for IV fluids or medications. It’s estimated that between 4 and 28% of inserted PIVCs are never used at all (ACSQHC 2021).

There are even reports of patients being discharged home with an IV in place because no one noticed it was there! (TheNursePath 2016)

PIVCs are often left in ‘just in case’ patients might need them. However, any IV cannula leads directly to the bloodstream and can be a source of infection. In fact, up to 69% of PIVCs are associated with complications (ACSQHC 2021).

Assess the need for the PIVC at least daily. If it wasn’t used in the past 24 hours or is not likely to be used in the next 24 hours, it should come out immediately (ACSQHC 2021).

Is the Cannula Working?

When a PIVC is inserted, a flashback of blood in the chamber confirms it’s in the vein. Afterwards, the cannula location is estimated by the flow of IV fluids (either by infusion pump or gravity) and/or IV flushes (manual injection).

Flushing the PIVC using an appropriate solution (refer to current evidence-based or best-practice guidelines) and at a frequency specified by your organiation’s policies and procedures decreases the risk of blockage, maintains patency and prevents incompatible medicines or fluids from being mixed (ACSQHC 2021).

At least once per shift or every eight hours, the PIVC should be assessed by checking for:

- Pain, swelling or redness around the PIVC site

- Any signs of infection, e.g. fever

- Leakage or occlusion at the PIVC site

- Hardening or thrombosis of the veins

- Dressing integrity and whether the PIVC is appropriately secured.

(ACSQHC 2021)

Resistance or failure to flush or flow indicates the PIVC might be kinked or blocked, or could have migrated out of the vessel (Goossens 2015).

Is the Cannula Tolerated by the Patient?

Provide explanations and education about the treatment, and check the patient’s (and their family’s) understanding. Ensure the patient knows why the PIVC is in, and encourage them to speak up if there are any problems, such as pain, leaking or swelling.

The PIVC should not be painful. Pain is a sign of phlebitis (inflammation of the vein) and means that the PIVC is not working well and should be removed (SESLHD 2022).

You may need to consider the use of an alternative device, such as a peripherally inserted central catheter (ACSQHC 2021).

An Irish study found that patients were seven times more likely to have a PIVC left in, unused, when they did not know why it was there (McHugh et al. 2011).

Involving the patient and family empowers them to voice their concerns, and prompts nurses to address problems and remove unused PIVCs.

Is the Cannula Appropriately Dressed and Secured?

A sterile, transparent, semipermeable dressing should be used to secure the PIVC (ACSQHC 2021).

Dressings must be clean, dry and intact to prevent microbial contamination of the site. Change the PIVC dressing if it becomes damp, loose, or visibly soiled (ACSQHC 2021).

A cross-sectional study of 51 countries found that 20% of PIVC dressings were substandard (ACSQHC 2021).

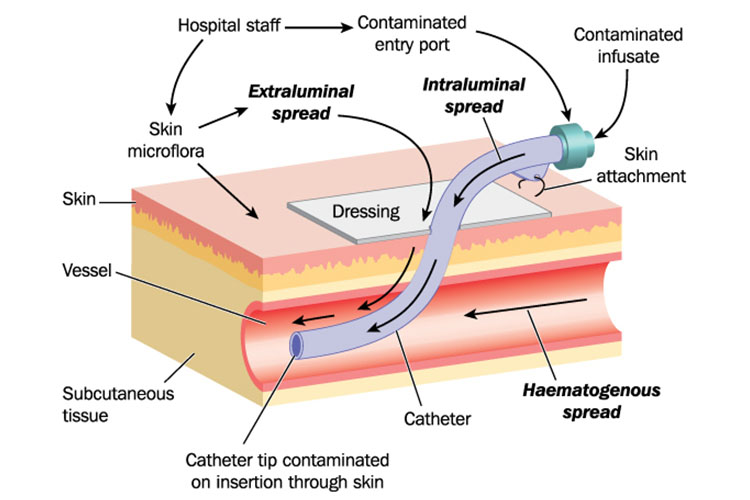

A poorly secured PIVC encourages infection, as cannula movement in the vein can allow migration of organisms along the cannula and into the bloodstream (Marsh et al. 2015).

Any Signs of Infection?

PIVCs are so common it’s easy to forget they pose an infection risk.

Standard precautions and Aseptic Non Touch Technique are essential when caring for a PIVC. Needleless connectors should be decontaminated with 70% alcohol and left to fully air dry before and after being accessed (ACSQHC 2021).

Don’t forget about possible bloodstream infection. If a patient has signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (fever, elevated heart rate etc.), any invasive device is a possible cause (Shah et al. 2013), and insertion sites should be examined for inflammation or purulence. If a patient shows signs of infection with no obvious source, consider removing the PIVC.

Any Other Complications?

Unfortunately, up to 90% of PIVCs are removed before treatment completion due to complications, most commonly dislodgment, occlusion, infiltration or phlebitis (ACSQHC 2019a; 2021).

Cannula failure often means painful and time-consuming replacement of the PIVC, which can be tricky, especially for paediatrics, older adults and patients with a lack of viable veins.

Many hospitals have implemented phlebitis scales such as the visual infusion phlebitis (VIP) score to improve PIVC assessment (ACSQHC 2019b).

Common IV cannula complications:

- Phlebitis (inflammation of the vein) is characterised by one or more of the following: pain, redness, swelling, warmth, a red streak along the vein, hardness of the IV site and/or purulence.

- Infiltration is the leakage of a non-vesicant solution into the surrounding tissues, causing pain and swelling.

- Extravasation is the migration into the tissues of a vesicant medicine or fluid, such as chemotherapy. This can be severely painful and cause major tissue trauma.

- Thrombosis or thrombophlebitis is the formation of a clot in the vessel, often caused by the cannula moving around in the vein and aggravating the vessel wall.

- Nerve damage can occur during PIVC insertion. If the patient complains of a sharp pain shooting up the arm, or ongoing numbness or tingling of the extremity, the cannula should be removed immediately.

- Partial or complete dislodgement of the PIVC indicates it is no longer in the vessel and must be removed.

(ACSQHC 2019a; Kaur et al. 2019)

Early detection and treatment of complications can prevent long-term consequences.

If infiltration or extravasation is suspected, stop the infusion immediately and attempt to aspirate the residual drug from the device (RCHM 2020).

If the site is swollen or painful, elevate the limb, seek medical advice and apply a hot or cold compress, depending on the agent. Offer pain relief, unless contraindicated. Continue to assess regularly, and document your assessment and actions, and the patient’s response (SCHN 2023).

Finally, remember that post-infusion phlebitis can occur up to 48 hours after a PIVC has been removed (Queensland Health 2015), so it’s important to assess old IV sites, as well as current sites.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

What should you do with a PIVC that hasn't been used in the past 24 hours and is not likely to be used in the next 24 hours?

Topics

References

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2019b, Infections Associated With Peripheral Venous Access Devices: A Rapid Review of the Literature, Australian Government, viewed 23 June 2023, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/infections-associated-peripheral-venous-access-devices-rapid-review-literature

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2021, Management of Peripheral Intravenous Catheters Clinical Care Standard, Australian Government, viewed 23 June 2023, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-05/management_of_peripheral_intravenous_catheters_clinical_care_standard_-_accessible_pdf.pdf

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2019a, Peripheral Intravenous Catheters: A Review of Guidelines and Research, Australian Government, viewed 23 June 2023, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-06/literature-review-peripheral-intravenous-catheters-a-review-of-guidelines-and-research_qut.pdf

- Goossens, GA 2015, ‘Flushing and Locking of Venous Catheters: Available Evidence and Evidence Deficit’, Nursing Research and Practice, viewed 23 June 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4446496/

- Kaur, P, Rickard, C, Domer, G S & Glover, K R 2019, ‘Dangers of Peripheral Intravenous Catheterization: The Forgotten Tourniquet and Other Patient Safety Considerations’, Vignettes in Patient Safety, vol. 4, viewed 23 June 2023, https://www.intechopen.com/books/vignettes-in-patient-safety-volume-4/dangers-of-peripheral-intravenous-catheterization-the-forgotten-tourniquet-and-other-patient-safety-

- Marsh, N, Webster, J, Mihala, G & Rickard, CM 2015, ‘Devices and Dressings to Secure Peripheral Venous Catheters to Prevent Complications’, The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, vol. 12, no. 6, viewed 23 June 2023, https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011070.pub2/full

- McHugh, SM et al. 2011, ‘Role of Patient Awareness in Prevention of Peripheral Vascular Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection’, Infection Control & Hospital Epdemiology, vol. 32, no. 1, viewed 23 June 2023, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/infection-control-and-hospital-epidemiology/article/abs/role-of-patient-awareness-in-prevention-of-peripheral-vascular-catheterrelated-bloodstream-infection/DDF84D7CC5CA66911CE5EFBF52447130

- TheNursePath 2016, ‘You Forgot to Remove the Cannula From Your Patient’s Arm. Now What?’, TheNursePath, 6 December, viewed 23 June 2023, https://thenursepathblog.wordpress.com/2016/12/06/you-forgot-to-remove-the-cannula-from-your-patients-arm-now-what/

- Queensland Health 2015, Peripheral Intravenous Catheter (PIVC), Queensland Government, viewed 23 June 2023, https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/444490/icare-pivc-guideline.pdf

- The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne 2020, Peripheral Extravasation Injuries: Initial Management and Washout Procedure, RCHM, viewed 23 June 2023, https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/Peripheral_Extravasation_Injuries__Initial_management_and_washout_procedure/

- Shah, H, Bosch, W, Thompson, KM & Hellinger, WC 2013, ‘Intravascular Catheter-related Bloodstream Infection’, Neurohospitalist, vol. 3, no. 3, viewed 23 June 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3805442/

- South Eastern Sydney Local Health District 2022, Peripheral Intravenous Cannulation (PIVC) Insertion, Care and Removal (Adults), New South Wales Government, viewed 23 June 2023, https://www.seslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/SESLHDPR%20577%20-%20Peripheral%20Intravenous%20Cannulation%20%28PIVC%29%20Insertion%2C%20Care%20and%20Removal%20%28Adults%29.pdf

- Sydney Children’s Hospital Network 2023, IV Extravasation Management Practice Guideline, SCHN, viewed 23 June 2023, https://resources.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/policies/pdf/2016-9057.pdf

New

New