What is Non-Invasive Ventilation (NIV)?

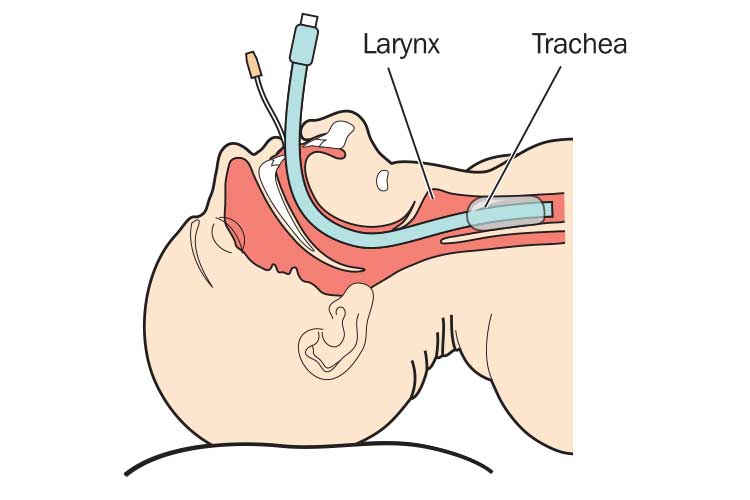

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is the delivery of respiratory support to a patient using an external interface (mask or helmet).

Unlike invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), which involves the insertion of an artificial airway (endotracheal tube or tracheostomy), NIV does not interfere with the patient’s upper airways and preserves their ability to speak, cough and swallow (Soo Hoo 2020; Gregoretti 2015).

NIV may be administered to a patient who is having difficulty ventilating and oxygenating due to acute respiratory distress, chronic respiratory conditions, surgical complications, asthma, comfort care or another respiratory failure. It may also be used to wean a patient off mechanical ventilation (ACI 2023).

NIV should be considered in the early stages of respiratory decline to minimise intensive care admission.

Benefits of Non-Invasive Ventilation

NIV may alleviate some of the physiological effects of respiratory failure, including reducing work of breathing and reversing hypoxia (Nickson 2024).

Early and successful implementation of NIV has been shown to decrease intubation rates and reduce the duration of intensive care unit and hospital stays. Furthermore, NIV has also been attributed to reduced rates of in-hospital morbidity and mortality (Comellini et al. 2019).

However, early detection of patient deterioration is crucial to ensure that oxygenation and ventilation are optimised.

NIV may also avert the risk of developing infections and complications associated with IMV such as pneumonia (Gregoretti 2015).

Non-Invasive Ventilation Interfaces

Successful implementation of NIV has been attributed to choosing an appropriate interface for the patient and providing adequate education to the patient to promote comfort and adherence to the device. The four types of interfaces used include:

- Oronasal mask (covers the nose and mouth)

- Nasal mask (covers the nose only)

- Full face mask (covers the whole face)

- Helmet (contains the patient’s head completely, with a seal around the neck).

(ACI 2023)

Each interface has advantages and disadvantages. Oronasal masks are generally preferable for patients with acute respiratory failure and are relatively successful, but they may be uncomfortable. Conversely, nasal masks are more comfortable but more likely to lead to NIV failure, often due to mouth leaks (ACI 2023).

It is important to be aware of factors that may contribute to interface intolerance by patients, including claustrophobia, poor fit, discomfort and oronasal dryness. Pressure injuries are common when using oro-nasal and nasal masks (ACI 2023).

How to Administer Non-Invasive Ventilation

Before delivering NIV, the patient must be assessed for:

- Capacity to protect their airway

- Level of consciousness

- Anticipated level of cooperation, comfort and adherence to the interface

- Capacity to manage their respiratory secretions

- Potential to recover the quality of life acceptable to the patient.

(ACI 2023)

If the patient fails to meet one of these criteria, they are ineligible for NIV and alternate care should be sought.

The process of administering NIV is as follows:

- Ensure the patient is sitting in an upright position.

- Conduct bed safety checks to ensure oxygen, suction, air viva etc. are working.

- Conduct a head-to-toe assessment. Continuous haemodynamic monitoring is essential.

- Ensure all necessary equipment is ready and connected.

- Provide education and reassurance to the patient about starting NIV, including how the mask or device may feel.

- Ensure face mask size is correct in order to maintain a tight seal.

- Proactive measures to prevent pressure injuries (e.g. hydrocolloid dressing) should be implemented prior to the commencement of NIV or as soon as possible. Additional strategies such as interface repositioning or interface changes may need to be implemented throughout the ventilation if a deterioration in skin integrity is observed.

- Silence all alarms when commencing NIV to decrease patient anxiety and noise around the bed area.

- Explain the therapy; provide additional patient education and reassurance on an ongoing basis. This is crucial to ensure therapy is successful and patient comfort and compliance are maintained.

- Start low and slow with machine settings to ensure the patient has time to adjust to the mask. You must listen to the patient and always maintain a calm approach as the environment may be stressful. Be aware that the patient may feel claustrophobic.

- Reassure the patient that it will be easy for them to breathe in with this therapy, as the air is readily available and will minimise their respiratory workload.

- Inform the patient that they must focus on breathing out slowly, as they will be faced with pressure that can potentially be uncomfortable (this will help keep the alveoli open and maximise oxygenation).

- Set the pressure of the inspiratory airway positive pressure (IPAP) and expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) at low levels initially and titrate to appropriate levels as per the observations of qualified nursing staff.

- Titrate oxygen concentration according to oxygen saturation and/or arterial blood gases to ensure therapy is effective.

- Continuous haemodynamic monitoring is essential.

- Provide ongoing education and reassurance for mask fit and comfort.

(ACI 2023; Rochwerg et al. 2017)

Possible Complications

Generally, NIV is tolerated well by most patients. However, adverse effects are possible (ACI 2023).

Patients who have a decreased level of consciousness secondary to raised carbon dioxide levels, or are confused or hypoxic, are at increased risk of developing complications and require constant observation until their condition improves (ACI 2023).

If the patient does not clinically improve after starting NIV, therapy may need to be escalated. If the patient continues to deteriorate despite therapy, call for assistance. The patient may need to be intubated and invasively ventilated (ACI 2023).

In the event of an escalation, the patient may be transferred to a critical care setting where higher staffing ratios and more complex interventions are available (ACI 2023).

Overall, nurse knowledge, understanding and communication, as well as patient comfort and compliance, are key in determining the success of NIV.

Note: This article is intended as a refresher and should not replace best-practice care. Always refer to your facility’s policy on non-invasive ventilation.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

What is a major advantage of non-invasive ventilation compared to mechanical ventilation?

Topics

Further your knowledge

References

- Agency for Clinical Innovation 2023, Non-invasive Ventilation Guidelines for Patients with Acute Respiratory Failure, New South Wales Government, viewed 16 April 2025, https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/820372/ACI-Non-invasive-ventilation-for-patients-with-acute-respiratory-failure.pdf

- Comellini, V, Pacilli, AMG & Nava, S 2019, ‘Benefits of Non‐invasive Ventilation in Acute Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure’, Respirology, vol. 24, no. 4, viewed 16 April 2025, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/resp.13469

- Gregoretti, C, Pisani, L, Cortegiani, A & Ranieri, VM 2015, ‘Noninvasive Ventilation in Critically Ill Patients’, Critical Care Clinics, vol. 31 no. 3, viewed 16 April 2025, https://www.criticalcare.theclinics.com/article/S0749-0704(15)00018-4/abstract

- Nickson, C 2024, Non-Invasive Ventilation (NIV), Life in the Fast Lane, viewed 16 April 2025, https://litfl.com/non-invasive-ventilation-niv/

- Rochwerg, B et al. 2017, ‘Official ERS/ATS Clinical Practice Guidelines: Noninvasive Ventilation for Acute Respiratory Failure’, Eur Respir J., vol. 50, no. 2, viewed 16 April 2025, https://www.thoracic.org/statements/resources/cc/niv-guidelines.pdf

- Soo Hoo, GW 2020, Noninvasive Ventilation, Medscape, viewed 16 April 2025, https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/304235-overview

New

New