Meningococcal disease is a highly uncommon illness, affecting only 0.5 people per 100,000 in Australia according to the most recent available data (Lahra et al. 2024).

Despite its rarity, meningococcal disease is a medical emergency with a 5 to 10% mortality rate and requires immediate diagnosis and treatment (Better Health Channel 2024).

What is Meningococcal Disease?

Meningococcal disease is a bacterial infection that typically presents as one or both of:

- Meningococcal meningitis (bacterial infection of the membranes of the brain and spinal cord)

- Meningococcal septicaemia (bacterial infection of the bloodstream).

(Queensland Government 2024)

In rare cases, it may lead to other localised infections including pneumonia, arthritis or conjunctivitis (AIH 2024).

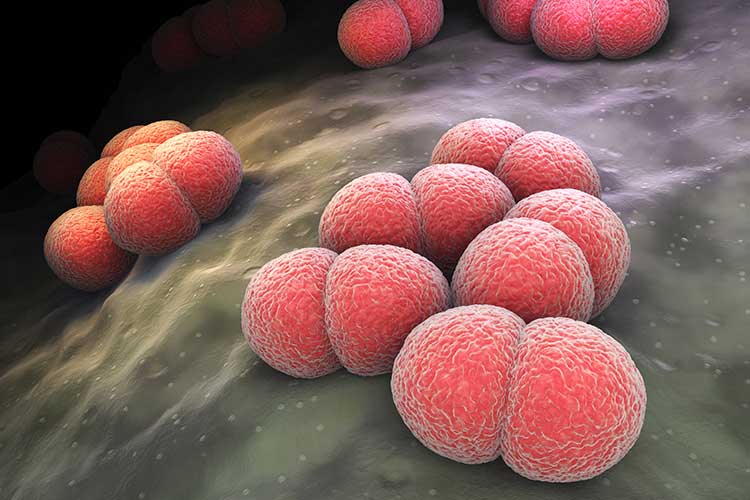

Meningococcal disease is caused by a bacterium known as Neisseria meningitidis. The bacteria has 13 serogroups (strains), each labelled by a particular letter of the alphabet. Strains A, B, C, W and Y most commonly cause illness (Better Health Channel 2024).

The most dominant serogroup in Australia is MenB, which accounts for over 80% of all meningococcal infections. MenC was once highly prevalent but was greatly reduced by the introduction of the Meningococcal C vaccine in 2003. The prevalence of MenW and MenY has increased since 2013 (Lahra et al. 2024).

What Causes Meningococcal Disease?

Neisseria meningitidis bacteria naturally dwell in the nose and throat of about 10% of people at any given time without causing illness (Better Health Channel 2024).

These carriers can spread N. meningitidis to other people via respiratory secretions such as coughing, sneezing or kissing. Despite this, it is not easily transmitted without prolonged or intimate contact with an infected person’s mucous because it can only survive outside of the human body for a few seconds (Healthy WA 2018; Better Health Channel 2024).

Therefore, N. meningitidis is most commonly spread from one person to another via:

- Living in the same household as an infected person

- Sexual contact

- Attending childcare with an infected person for more than four continuous hours.

(Healthy WA 2018)

While it is also possible to transmit the bacteria by sharing food and drinks, this is highly unlikely due to the bacteria’s short lifespan outside the body. Furthermore, it cannot be transmitted by touching contaminated surfaces or objects because it dies too quickly (Healthy WA 2018).

In most cases, when someone acquires N. meningitidis, their body produces sufficient antibodies to contain the infection and prevent it from spreading (Oakley 2014).

However, in rare cases, the bacteria become invasive, spread and cause serious illness (Healthdirect 2023). This may occur if the person doesn’t have enough time to build up antibodies, or if they have a compromised immune system (Oakley 2014).

Those most likely to be carriers are adolescents and young adults, not due to their age itself but rather, due to social behaviours that increase the risk of transmission such as living in dormitories or military barracks, smoking, deep kissing and visiting bars (Burman et al. 2018).

Risk Factors For Meningococcal Disease

While meningococcal disease can affect anyone, those who are at increased risk include:

- Children under two years of age

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples aged between 2 months and 19 years

- Adolescents and young adults aged between 15 and 24 years

- People who live with others in close quarters (e.g. university dormitories or military barracks)

- People with certain conditions that increase their risk of meningococcal disease (e.g. certain blood disorders or a compromised immune system)

- People living with others who have meningococcal disease

- People who smoke or are exposed to tobacco smoke

- People who have recently experienced a viral upper respiratory tract infection

- Travellers to countries where there are high rates of meningococcal disease

- Laboratory workers who handle Neisseria meningitidis bacteria.

(Healthdirect 2024; Better Health Channel 2024; AIH 2024)

Symptoms of Meningococcal Disease

Most symptoms of meningococcal disease are non-specific, especially in young children, and often have a sudden onset (NSW Health 2024). The incubation period is between 1 and 10 days (VIC DoH 2025).

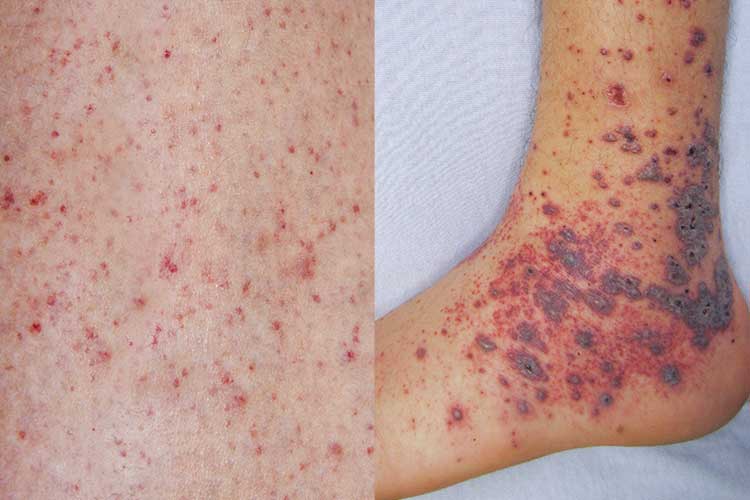

The characteristic rash, which presents as petechiae (small red or purple spots) or purpura (resembles reddish-purple bruising), is a common symptom occurring in 50 to 75% of meningococcal septicaemia cases (Oakley 2014). It’s caused by bleeding under the skin and is one of the clearest and most important signs that a person has meningococcal disease and requires urgent treatment (Carter 2019).

Other possible symptoms include:

| Adults and older children | Babies and younger children |

|---|---|

|

|

(Better Health Channel 2024; RCHM 2018)

Diagnosing Meningococcal Disease

Any person displaying the symptoms of meningococcal disease must be diagnosed as soon as possible. Diagnosis involves taking blood and cerebrospinal fluid cultures (Better Health Channel 2024).

Treating Meningococcal Disease

Meningococcal disease can become fatal just hours after the onset of symptoms, with meningococcal septicaemia being one of the most rapidly-killing infectious diseases (Oakley 2014).

Intravenous antibiotic treatment (typically benzylpenicillin and/or a third-generation ceftriaxone/cefotaxime) and supportive care in hospital must be commenced as urgently as possible to maximise the patient’s chance of survival. Due to the severity of the illness, antibiotics are usually administered even before the diagnosis has been confirmed (SA Health 2023; Siddiqui et al. 2023; RCHM 2020).

Complications of Meningococcal Disease

Despite the severity of the disease, many people with meningococcal disease make a full recovery. However, about 30 to 40% of cases result in long-term complications or disability (AIH 2024).

Potential long-term complications of meningococcal disease can include:

- Limb loss or deformation due to skin and tissue necrosis

- Scarring on the skin

- Deafness or hearing loss in one or both ears

- Blindness

- Learning difficulties

- Neurological issues

- Seizures.

(AIH 2024; Healthdirect 2024; Better Health Channel 2024)

Preventing Meningococcal Disease

The best way to prevent meningococcal disease is via vaccination. There are three types of meningococcal vaccine in Australia:

- Meningococcal B vaccine (protects against serogroup B)

- Meningococcal C vaccine (protects against serogroup C)

- Meningococcal ACWY vaccine (protects against serogroups A, C, W and Y).

(AIH 2022)

The Australian Immunisation Handbook recommends that any person over the age of 6 weeks who wishes to protect themselves against meningococcal disease receives both the MenB and MenACWY vaccines (AIH 2024).

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

What type of infection is meningococcal disease?

Topics

References

- Australian Immunisation Handbook 2024, Meningococcal Disease, Australian Government, viewed 9 April 2025, https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/vaccine-preventable-diseases/meningococcal-disease

- Better Health Channel 2024, Meningococcal Disease, Victoria State Government, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/meningococcal-disease

- Burman, C, Serra, L, Nuttens, C, Presa, J, Balmer, P & York, L 2018, ‘Meningococcal Disease in Adolescents and Young Adults: a Review of the Rationale for Prevention Through Vaccination’, Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, vol. 15, no. 2, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6422514/

- Carter, K 2019, ‘What is the 'Meningitis Rash'?’, Meningitis Research Foundation Blog, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.meningitis.org/blogs/what-is-the-meningitis-rash

- Healthdirect 2023, Meningococcal Disease, Australian Government, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/meningococcal-disease

- Victoria Department of Health 2025, Meningococcal Disease, Victoria State Government, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.health.vic.gov.au/infectious-diseases/meningococcal-disease

- Healthy WA 2018, Meningococcal Disease, Government of Western Australia, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.healthywa.wa.gov.au/Articles/J_M/Meningococcal-disease

- Lahra, MM, George, CRR, van Hal, S & Hogan, TR 2024, ‘Australian Meningococcal Surveillance Programme Annual Report, 2023’, Communicable Diseases Intelligence, vol. 48, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/CA1DBF11D71F5F3ECA258ADE0019B036/$File/cdi-2024-48-52.pdf

- NSW Health 2024, Meningococcal Disease Fact Sheet, New South Wales Government, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/factsheets/Pages/meningococcal_disease.aspx

- Oakley, A 2014, Meningococcal Disease, DermNet, viewed 9 April 2025, https://dermnetnz.org/topics/meningococcal-disease

- Queensland Government 2024, Meningococcal Disease, Queensland Government, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.qld.gov.au/health/condition/infections-and-parasites/bacterial-infections/meningococcal-disease

- Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne 2018, Meningococcal Infection, RCHM, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.rch.org.au/kidsinfo/fact_sheets/Meningococcal_infection/

- Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne 2020, Clinical Practice Guidelines: Acute Meningococcal Disease, RCHM, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/acute_meningococcal_disease/

- SA Health 2023, Meningococcal Disease (Invasive) for Health Professionals, Government of South Australia, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/clinical+resources/clinical+programs+and+practice+guidelines/infectious+disease+control/meningococcal+disease+invasive/meningococcal+disease+invasive+for+health+professionals

- Siddiqui, JA, Ameer, MA & Gulick, PG 2023, ‘Meningococcemia’, StatPearls, viewed 9 April 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534849/

New

New