About 16% of Australians (4 million) are currently affected by back problems, and about 70 to 90% of people are expected to experience low back pain at some point during their lifetime (AIHW 2023; ACSQHC 2021).

Back pain is a leading cause of disability that may adversely affect all aspects of daily functioning (Mayo Clinic 2023; Better Health Channel 2019). Between 10 and 40% of adults with low back pain are estimated to experience persistent and disabling symptoms (Wheeler et al. 2018).

Despite the prevalence of low back pain in the community, research suggests that 28% of healthcare for low back pain in Australia does not follow clinical guidelines. Often, the mismanagement of low back pain involves unnecessary treatments that do more harm than good (Wheeler et al. 2018).

Effectively managing low back pain is therefore essential in ensuring patients are able to enjoy a high quality of life.

What is Low Back Pain?

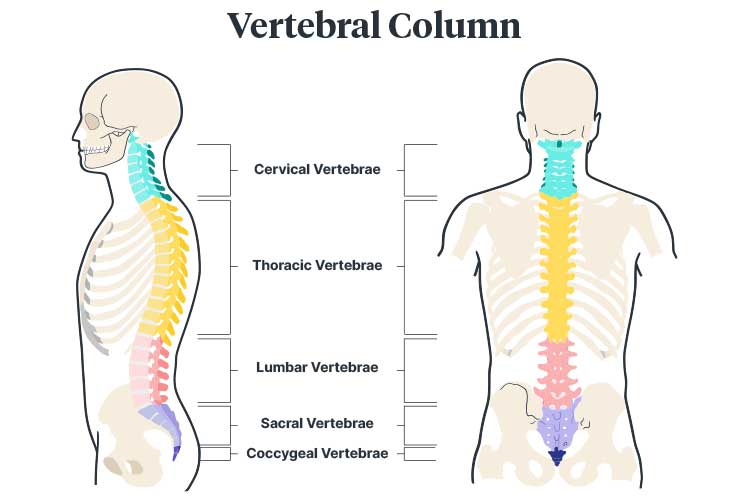

The spine is comprised of bones known as vertebrae, which stack on top of one another to form a column in the shape of an ‘S’ (Better Health Channel 2019).

Low back pain affects the lumbar spine, which comprises the vertebrae L1, L2, L3, L4 and L5. The lumbar spine carries significant weight from the upper body (NINDS 2020).

Most low back pain is acute, lasting between a few days to a few weeks. However, in some cases, it may become chronic, persisting for 12 weeks or more even after the initial cause has been treated (NINDS 2020).

Causes of Low Back Pain

While there are many potential causes of low back pain, it usually originates from the muscles, ligaments, and joints rather than being caused by damage to the spine itself (Better Health Channel 2019).

Occasionally, low back pain is caused by:

- Medical conditions such as sciatica, a slipped disc, ankylosing spondylitis, spondylolisthesis, arthritis, whiplash, osteoporosis, or a muscle or ligament strain

- Serious conditions such as a broken bone in the spine, an infection, or cancer.

(Better Health Channel 2019; Healthdirect 2023)

However, only about 8 to 15% of low back pain has a particular pathoanatomical cause. Most low back pain is instead classified as ‘non-specific’ (Wheeler et al. 2018).

The most common causes of low back pain are ‘triggers’ such as:

- Manual handling

- Bending awkwardly

- Lifting, carrying, pushing, or pulling objects incorrectly

- Repetitive actions (bending, lifting, or sitting)

- Bad posture (slouching or being hunched over)

- Standing or bending down for a prolonged period of time

- Twisting

- Overstretching

- Driving for a prolonged period of time

- Overusing muscles (e.g., due to sport or repetitive movements)

- Exposure to whole-body vibration

- Muscle tension from stress

- Lack of physical activity.

(Healthdirect 2023; Better Health Channel 2019)

Risk Factors for Low Back Pain

Risk factors for low back pain include:

- Being overweight (as this puts more pressure on the spine)

- Lack of exercise

- Smoking (which may damage tissues in the back or indicate an unhealthy lifestyle overall)

- Pregnancy (as this puts more pressure on the spine)

- Prolonged use of medicines that weaken bones, such as corticosteroids

- Stress (which may cause muscle tension in the back)

- Depression (this may cause a cycle wherein back pain causes feelings of depression, leading the patient to gain weight, which then further exacerbates the pain and continues the cycle).

(Healthdirect 2023)

Symptoms of Low Back Pain

Low back pain varies depending on the cause. Onset may be sudden or gradual, and symptoms may range from mild to debilitating. Furthermore, the pain may be dull or sharp in intensity (Peloza 2017; NINDS 2020).

Symptoms may include:

- Dull, achy pain in the low back

- Stinging, burning pain that travels from the low back to the thighs, lower legs, or feet and may include numbness or tingling (sciatica)

- Tightness and muscle spasms in the low back, pelvis, or hips

- Pain that is exacerbated by standing or sitting

- Difficulty standing up straight, walking, or getting up from a seated position

- Psychological symptoms such as distress, anxiety, and mood issues if the pain is prolonged.

(Peloza 2017; Better Health Channel 2019)

The following symptoms may indicate a serious underlying problem:

- Incontinence

- Numbness near the rectum or genitals

- Numbness, pins and needles, or weakness in the legs

- Unsteadiness

- Unexplained weight loss

- Night sweats

- Chills

- Fever

- Nausea and vomiting

- Unrelenting pain at night.

(SA Health 2022)

Anyone experiencing any of the above symptoms is encouraged to seek medical advice immediately (SA Health 2022).

Investigating Low Back Pain

A major issue regarding the care of patients with low back pain is the unnecessary use of spinal imaging to assist in diagnosis or rule out a serious medical condition (Wheeler et al. 2018).

While routine spinal imaging might seem like an effective way to reassure patients, it has actually been found to decrease patients’ sense of wellbeing and cause unnecessary anxiety. Patients may become concerned about age-related degenerative changes that are found through imaging, causing them to be fearful or avoidant. These behaviors, in turn, may increase the patient’s disability (Wheeler et al. 2018).

Furthermore, unless ‘red flag’ signs or symptoms are present, a serious medical problem is unlikely. In many cases, patients are referred for spinal imaging when there is no evidence it will benefit them (Wheeler et al. 2018).

Patients who receive high-quality education without unnecessary imaging are more likely to have a positive outcome (Wheeler et al. 2018).

Managing Low Back Pain

International guidelines for the clinical care of low back pain are generally consistent (Wheeler et al. 2018). The general consensus regarding care is that:

- First-step care should comprise encouraging the patient to stay active, providing high-quality education and reassuring the patient that there is no serious disease present.

- Second-step care for acute low back pain should comprise at least one of the following: physical therapy, psychological therapy, and complementary therapy.

- Second-step care for chronic low back pain should comprise physical therapy, psychological therapy, and/or complementary therapy.

- Third-step care for chronic low back pain should comprise interprofessional pain management.

- Low back pain should preferably be treated without the use of medicines. If pain medicine is required, however, first-line treatment should be a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicine at the lowest effective dose for the shortest time possible. Note: This should only be discussed with the patient if you are a healthcare professional who is qualified to do so.

- Opioids should be avoided as a treatment option where possible.

- Patients with chronic, non-specific low back pain should not be offered injectable steroid medicines.

- Routine spinal imaging should be avoided unless ‘red flag’ signs or symptoms are present.

(Traeger et al. 2019)

Overall, evidence suggests that unnecessary care (spinal imaging, spinal injections, hospitalisation, and surgery) adversely affects patients in most cases (Traeger et al. 2019).

Therefore, when investigating and managing low back pain, it is important to:

- Communicate with the patient in a positive way

- Encourage the patient to return to normal activity as soon as possible, as most low back pain improves after four to six weeks

- If imaging is required, refer to evidence-based guidelines when educating the patient

- Remember that radiological abnormalities are common and are not necessarily related to the pain

- If imaging finds age-related changes, explain these to the patient using reassuring, non-threatening language, and provide epidemiological context

- Refer to other healthcare professionals if needed.

The Low Back Pain Clinical Care Standard

The Low Back Pain Clinical Care Standard was released by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care in 2022.

This standard aims to enhance the early assessment, management, review, and referral of low back pain and reduce the use of unnecessary, ineffective, and harmful treatments (ACSQHC 2022).

The standard comprises the following eight Quality Statements:

| Quality Statement | Description |

|---|---|

| 1: Initial clinical assessment | Assessment for patients presenting with new low back pain should centre on potential underlying conditions and take into account psychological and social factors. The assessment should include a thorough history and physical assessment, along with a neurological examination if indicated. |

| 2: Psychosocial assessment | Patients presenting with new low back pain should undergo an assessment of psychosocial factors that may affect their recovery. This assessment will be repeated during future visits in order to monitor their progress. |

| 3: Reserve imaging for suspected serious pathology | In order to reduce unnecessary patient distress and radiation exposure, imaging should only be performed when a serious underlying cause for low back pain is suspected. |

| 4: Patient education and advice | Patients should be appropriately informed about their condition and the benefits, risks and costs of their treatment options. |

| 5: Encourage self-management and physical activity | Patients should be supported to remain active and return to their usual daily activities as soon as they can. Clinicians should work with patients to develop a self-management plan for increasing function and reducing the impact of pain. |

| 6: Physical and/or psychological interventions | Patients should be offered physical and/or psychological interventions when indicated. Treatments should focus on removing barriers to recovery. |

| 7: Judicious use of pain medicines | Medicines should be prescribed with the goal of enabling physical activity rather than preventing pain. They must be prescribed according to the Therapeutic Guidelines and regularly reviewed. Anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines and antidepressants should not be prescribed for low back pain, while opioid analgesics should only be prescribed for carefully chosen patients, at the lowest dose for the shortest possible length of time. |

| 8: Review and referral | Patients who are experiencing persisting or worsening symptoms should be reassessed early so that any barriers to improvement can be identified. These patients may require referral for an interprofessional approach and, in certain cases, a specialist medical or surgical review. |

(ACSQHC 2022)

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

True or false: Most low back pain requires spinal imaging to rule out the possibility of a serious medical issue.

Topics

References

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2021, Action on Low Back Pain, Australian Government, viewed 6 February 2024, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/newsroom/external-publications/action-low-back-pain

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2022, Low Back Pain Clinical Care Standard (2022), Australian Government, viewed 7 February 2024, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/low-back-pain-clinical-care-standard-2022

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023, Chronic Musculoskeletal Conditions: Back Problems, Australian Government, viewed 6 February 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/back-problems

- Better Health Channel 2019, Back Pain, Victoria State Government, viewed 6 February 2024, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/Back-pain

- Healthdirect 2023, Back Pain, Australian Government, viewed 6 February 2024, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/back-pain

- Mayo Clinic 2023, Back Pain, Mayo Clinic, viewed 6 February 2024, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/back-pain/symptoms-causes/syc-20369906

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke 2020, Low Back Pain Fact Sheet, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, viewed 6 February 2024, https://www.ninds.nih.gov/sites/default/files/migrate-documents/low_back_pain_20-ns-5161_march_2020_508c.pdf

- Peloza, J 2017, Lower Back Pain Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment, Spine-health, viewed 6 February 2024, https://www.spine-health.com/conditions/lower-back-pain/lower-back-pain-symptoms-diagnosis-and-treatment

- SA Health 2022, Low Back Pain, Government of South Australia, viewed 6 February 2024, https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/conditions/pain/low+back+pain/low+back+pain

- Traeger, AC, Buchbinder, R, Elshaug, AG, Croft, PR & Maher, CG 2019, ‘Care for Low Back Pain: Can Health Systems Deliver?’, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, vol. 97, no. 423-433, viewed 7 February 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6560373/

- Wheeler, LP, Karran, EL & Harvie, DS 2018, ‘Low Back Pain: Can we Mitigate the Inadvertent Psycho-behavioural Harms of Spinal Imaging?’, Australian Journal of General Practice, vol. 47, no. 9, viewed 6 February 2024, https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2018/september/low-back-pain

New

New