Did you know that over 30% of deaths in the Western world can be attributed to acute coronary syndromes (Nickson 2021)?

Furthermore, in Australia, over 200 people are admitted to hospital every day for acute coronary syndrome (ACSQHC 2019).

What are Acute Coronary Syndromes?

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is an umbrella term used to describe any situation where the blood supply to the heart is suddenly obstructed (AHA 2022).

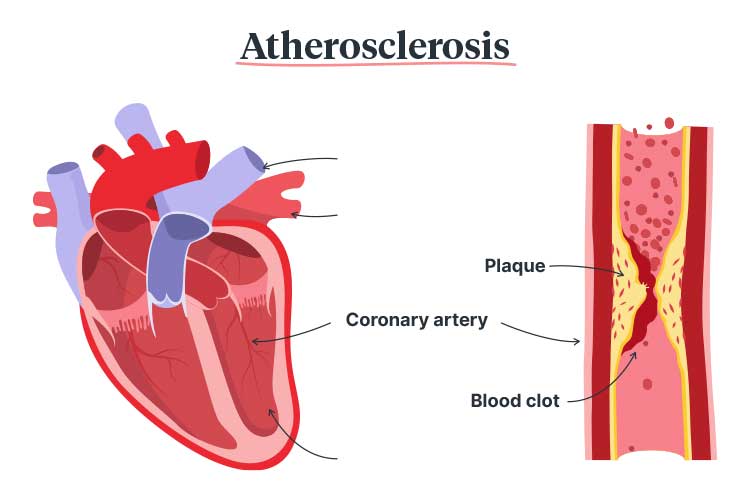

In most cases, the blockage is caused by a thrombosis that decreases blood supply to part of the heart muscle (ACSQHC 2019).

The primary cause of an ACS is atherosclerosis (also known as coronary heart disease), a condition where plaque (made up of cholesterol and fatty materials) builds up and thickens the artery walls (ACSQHC 2019; Shahjehan & Bhutta 2023).

In some cases, an ACS is caused by the spasming and narrowing of the arteries, which impedes blood supply, or spontaneous coronary artery dissection, which occurs when the coronary artery wall tears (Heart Foundation 2023).

If not treated properly, an ACS can be life-threatening (ACSQHC 2019).

Types of Acute Coronary Syndromes

Acute coronary syndromes include:

- Unstable angina

- Acute myocardial infarction

- S-T segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

- Non-S-T segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS)

- Non-S-T segment elevation myocardial infarction (Non-STEMI)

(ACSQHC 2019; Nickson 2021)

Unstable angina describes chest pain caused by an obstructed blood supply to the heart. This may progress into an acute myocardial infarction, which occurs when the blockage injures or causes the death of the heart muscle (ACSQHC 2019).

Issues Surrounding Acute Coronary Syndromes in Australia

Certain patients are less likely to receive appropriate interventions (especially invasive management) for an ACS, even if they have been recommended. These include:

- Women, due to atherosclerosis being stereotyped as a ‘men’s disease’. This may lead to underestimation of risk when caring for female patients, and consequently, they may receive more conservative treatments.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, due to factors such as:

- Language barriers

- Lack of coordinated care

- Failure of healthcare workers to discuss recommended interventions with patients’ family members

- Lack of cultural safety

- People who live in remote areas due to logistical factors.

(ACSQHC 2019; Worrall-Carter et al. 2016; Walsh & Kangaharan 2017; Chew et al. 2013)

These are some of the issues that informed the development of the Acute Coronary Syndromes Clinical Care Standard.

Risk Factors for Acute Coronary Syndromes

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- High blood cholesterol

- Lipids

- Family history of atherosclerosis

- Being male

- Obesity

- Previous myocardial infarction

- Receiving hormone replacement for menopause

- Lack of activity

- Smoking

- A family history of chest pain, heart disease or stroke.

(Nickson 2021; AHA 2022)

Symptoms of Acute Coronary Syndromes

The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort, which may feel like pressure, tightness, burning or aching (Mayo Clinic 2023). Other possible symptoms include:

- Pain or discomfort in the arms, jaw, neck, back or stomach

- Nausea or vomiting

- Indigestion

- Shortness of breath

- Diaphoresis

- Dizziness, lightheadedness or syncope

- Unexplained or abnormal fatigue

- Restlessness.

(Mayo Clinic 2023)

Note that the symptoms of an ACS often have a sudden onset (Mayo Clinic 2023).

Differential Diagnoses of Acute Coronary Syndromes

Non-ACS conditions that may cause acute chest pain include:

- Aortic dissection

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pericarditis and myocarditis

- Gastrointestinal conditions

- Musculoskeletal conditions

- Pulmonary diseases

- Sickle cell crisis

- Herpes zoster.

(Chew et al. 2016)

Even if 12-lead ECG does not indicate STEMI, other life-threatening conditions such as aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism and tension pneumothorax should be considered (Chew et al. 2016).

Acute Coronary Syndromes Clinical Care Standard

In 2019, the Australia Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care released the Acute Coronary Syndromes Clinical Care Standard. This standard aims to ensure all patients presenting with an ACS receive consistent and appropriate treatment (ACSQHC 2019).

The standard contains six quality statements that aim to guide the care of patients experiencing an ACS:

1. Immediate Management

Read: Chest Pain Assessment: What to Do When Your Patient Has Chest Pain

Patients who present with acute chest pain or other symptoms indicative of ACS are assessed using a documented chest pain assessment pathway. Patients should be appropriately informed and provide informed consent for treatment.

(ACSQHC 2019)

2. Early Assessment

Read: 12-lead ECG in the Field

Patients who present with acute chest pain or other symptoms indicative of an ACS should undergo a 12-lead ECG and have the results interpreted within 10 minutes of first emergency clinical contact. The ECG must be performed by an appropriately experienced clinician.

This is to ensure that ACSs are identified as soon as possible and treatment can be commenced.

(ACSQHC 2019)

3. Timely Reperfusion

Patients experiencing a STEMI should undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or fibrinolysis if emergency reperfusion is deemed clinically appropriate (ACSQHC 2019).

Based on the current Heart Foundation guidelines:

- Patients should receive percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) if it can be performed within 90 minutes of initial medical contact (under 90 minutes ‘door-to-balloon’ time), or

- Patients should receive fibrinolytic therapy if PCI can not be performed within 90 minutes of initial medical contact.

(Chew et al. 2016)

4. Risk Stratification

Patients experiencing an NSTEACS should be managed depending on their anticipated risk of severe cardiac issues in the future.

In order to evaluate this risk, the clinician may use risk assessment tools such as:

- GRACE ACS Risk Calculator

- TIMI Risk Score for UA/NSTEMI

- Decision-making and timing considerations in reperfusion for STEMI.

Any treatments should be planned using a shared decision-making process, and patients’ preferences should be taken into account.

(ACSQHC 2019)

5. Coronary Angiography

Coronary angiography is a procedure in which dye is released into the patient’s arteries. Through an x-ray, this dye is able to indicate the location and extent of arterial blockages.

It is recommended that patients experiencing an NSTEACS consider undergoing coronary angiography if the anticipated risk of severe cardiac issues in the future is medium or high.

(ACSQHC 2019)

6. Individualised Care Plan

Prior to discharge, patients who have experienced an ACS should work with clinicians to develop an individualised care plan containing:

- Lifestyle changes to manage risk factors

- Medicines to manage risk factors

- The patient’s psychosocial needs

- Referral to a rehabilitation clinic or prevention service.

Within 48 hours of discharge, a copy of this plan should be forwarded to the patient and their general practitioner or ongoing clinical provider.

(ACSQHC 2019)

Secondary prevention strategies such as lifestyle changes, medicines and rehabilitation are essential in reducing the risk of future adverse events (Chew et al. 2016).

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

If emergency reperfusion can not be performed within 90 minutes, what treatment should the patient generally receive?

Topics

References

- American Heart Association 2022, Acute Coronary Syndrome, AHA, viewed 12 February 2024, https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-attack/about-heart-attacks/acute-coronary-syndrome

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2019, Acute Coronary Syndromes Clinical Care Standard, Australian Government, viewed 12 February 2024, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/acute-coronary-syndromes-clinical-care-standard-2019

- Chew, DP et al. 2013, ‘Acute Coronary Syndrome Care Across Australia and New Zealand: The SNAPSHOT ACS Study’, The Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 199, no. 3, viewed 12 February 2024, https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2013/199/3/acute-coronary-syndrome-care-across-australia-and-new-zealand-snapshot-acs-study

- Chew, DP et al. 2016, ‘National Heart Foundation of Australia & Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Australian Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes 2016’, The Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 205 no. 3, viewed 12 February 2024, https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/Bundles/Your-heart/Conditions/fp-acs-guidelines

- Heart Foundation 2023, What is a Heart Attack?, Heart Foundation, viewed 12 February 2024, https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/conditions/heart-attack

- Mayo Clinic 2023, Acute Coronary Syndrome, Mayo Clinic, viewed 12 February 2024, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/acute-coronary-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20352136

- Nickson, C 2021, Acute Coronary Syndromes, Life in the Fast Lane, viewed 12 February 2024, https://litfl.com/acute-coronary-syndromes/

- Shahjehan, RD & Bhutta, BS 2023, ‘Coronary Artery Disease’, StatPearls, viewed 12 February 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564304/

- Walsh, WF & Kangaharan, N 2017, ‘Cardiac Care for Indigenous Australians: Practical Considerations from a Clinical Perspective’, The Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 207, no. 1, viewed 12 February 2024, https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2017/207/1/cardiac-care-indigenous-australians-practical-considerations-clinical

- Worrall-Carter, L, McEvedy, S, Wilson, A & Rahman, MA 2016, ‘Gender Differences in Presentation, Coronary Intervention, and Outcomes of 28,985 Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients in Victoria, Australia’, Women’s Health Issues, vol. 26, no. 1, viewed 12 February 2024, https://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(15)00136-X/fulltext

Additional Resources

- Acute Coronary Syndromes Clinical Care Standard | ACSQHC

- Australian Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes 2016 | National Heart Foundation of Australia & Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand

- 12-lead ECG in the Field | Ausmed Article

- Chest Pain Assessment: What to Do When Your Patient Has Chest Pain | Ausmed Article

New

New