This article will discuss how to assess acute pain in critically ill patients.

Pain should be predicted in all patients, and every action should be questioned for its possibility of causing pain or discomfort. Anticipating pain allows alternative strategies to be considered or pre-emptive analgesics given (Mallet et al. 2013).

What is Pain?

Pain is defined as ‘An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage’ (IASP 2020).

Causes of Pain in Critically Ill Patients

Between 40 and 77% of critically ill patients admitted to intensive care units are estimated to experience moderate to severe pain (Bhattacharyya et al. 2023).

Pain often occurs at rest and during standard care procedures, and can lead to adverse outcomes such as stress responses, cognitive impairment, impaired sleep and agitation (Seo et al. 2022).

Potential causes of pain in critically ill patients can include:

- Surgery

- Trauma

- Invasive procedures

- Intubation and extubation

- Nasogastric tubes

- Mechanical ventilation

- Nursing care such as repositioning, bathing and changing sheets

- Endotracheal suctioning

- Insertion of arterial lines, peripheral IVs and central venous catheters

- Drains/drain removal

- Peripheral blood draws

- Respiratory exercise

- Eye and mouth care

- Mobilisation.

(Pandharipande & Hayhurst 2024; Seo et al. 2022; Devlin et al. 2018)

Pain is often underreported in critically ill patients (Pandharipande & Hayhurst 2024). Therefore, patients should be assessed for pain regularly, and the frequency of assessment should be patient-specific and adjusted according to their risk.

Potential Barriers to Adequate Pain Management in Critically Ill Patients

A qualitative study by Bhattacharyya et al. (2023) identified several potential barriers to adequate pain management in ICU settings, including:

- Lack of knowledge of and/or trust in pain assessment tools

- High clinical workloads

- Pain not being viewed as a priority in critically ill patients

- Biases and assumptions of pain levels based on demographic factors (e.g. age, ethnicity)

- Lack of confidence in pain management abilities

- Difficulty communicating with patients who are sedated and/or experiencing delirium

- Concerns related to high-dose use of opioids.

The Effects of Untreated or Unmanaged Pain

Untreated pain can pose serious consequences for the already compromised critically ill patient, potentially leading to both short and long-term physical and psychological consequences such as:

- Stress responses, including tachycardia, hypercoagulation, respiratory compromise, immunosuppression, catabolism and increased myocardial oxygen consumption

- Increased length of stay in the ICU

- Increased duration of mechanical ventilation

- Wound infection

- Impaired sleep

- Exhaustion

- Disorientation

- Agitation

- Chronic pain

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

(Bhattacharyya et al. 2023; Seo et al. 2022)

Pain Assessment in the Critically Ill Patient

Careful consideration needs to be given to the assessment method chosen for critically ill patients because they are often unable to participate in the pain assessment process.

Below are some methods of assessing pain in critically ill patients:

Self-Report Tools

Self-report is considered the most reliable method of pain assessment (Health.vic 2024)

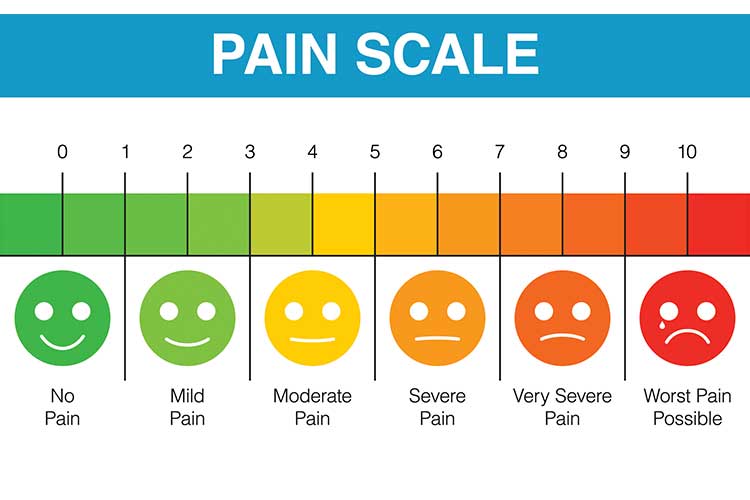

This method is offered to patients who are able to communicate, even if not verbally. A numerical rating scale (NRS) with a standard scale of 0-10 (where 0 = pain-free and 10 = worst pain you can imagine) can still be used if the patient is able to point to the scale or nod at simple commands (Nordness et al. 2021).

Other examples of self-report assessment tools include the verbal description scale (VDS) and the visual analogical scale (VAS)

Observational Tools

You may be unable to obtain a self-report from some critically ill patients due to factors such as sedation or delirium. In these cases, an observation of the patient’s pain behaviours can be used to measure pain instead (Chanques & Gélinas 2022).

The most reliable pain assessment tools for critically ill patients who cannot self-report are the behavioural pain scale (BPS) and the critical care observation pain tool (CPOT) (Seo et al. 2022).

The Behavioural Pain Scale (BPS)

| Facial expression | Relaxed | +1 |

| Partially tightened (e.g. brow lowering) | +2 | |

| Fully tightened (e.g. eyelid closing) | +3 | |

| Grimacing | +4 | |

| Upper limb movement | No movement | +1 |

| Partially bent | +2 | |

| Fully bent with finger flexion | +3 | |

| Permanently retracted | +4 | |

| Compliance with mechanical ventilation | Tolerating movement | +1 |

| Coughing, but tolerating ventilator for most of the time | +2 | |

| Fighting ventilator | +3 | |

| Unable to control ventilation | +4 |

(Adapted from Seo et al. 2022)

The scores from each of the three sections are added together:

| No pain | ≤ 3 |

| Mild pain | 4-5 |

| Unacceptable amount of pain | 6-11 |

| Maximum pain | ≥ 12 |

(Adapted from MDCalc n.d.)

Typically, a score of ≥6 indicates sedation and/or analgesia.

The Critical Care Observation Pain Tool (CPOT)

| Facial expression | No muscular tension observed | Relaxed, neutral | +0 |

| Presence of frowning, brow lowering, orbit tightening and levator contraction | Tense | +1 | |

| All of the above facial movements plus eyelid tightly closed | Grimacing | +2 | |

| Body movement | Does not move at all (does not necessarily mean absence of pain) | Absence of movements | +0 |

| Slow, cautious movements, touching or rubbing the pain site, seeking attention through movements | Protection | +1 | |

| Pulling tube, attempting to sit up, moving limbs/thrashing, not following commands, striking at staff, trying to climb out of bed | Restlessness | +2 | |

| Muscle tension: evaluating by passive flexion and extension of upper extremities | No resistance to passive movements | Relaxed | +0 |

| Resistance to passive movements | Tense, rigid | +1 | |

| Strong resistance to passive movement, inability to complete them | Very tense or rigid | +2 | |

| Compliance with the ventilator (intubated patients) OR | Alarms not activated, easy ventilation | Tolerating ventilator or movement | +0 |

| Alarms stop spontaneously | Coughing but tolerating | +1 | |

| Asynchrony: blocking ventilation, alarms frequently activated | Fighting ventilator | +2 | |

| Vocalisation (extubated patients) | Talking in normal tone or no sound | Talking in normal tone or no sound | +0 |

| Sighing, moaning | Sighing, moaning | +1 | |

| Crying out, sobbing | Crying out, sobbing | +2 |

(Adapted from Seo et al. 2022)

The total score of the CPOT will be between 0 and 8, where 0 ≤ 2 indicates no pain and > 2 indicates pain and the need for analgesia (Nazari et al. 2022).

Conclusion

Effective pain assessment is an important element of the nurses’ role. The effects of inadequate pain management are significant and can lead to delayed healing and prolonged recovery. The nurse, therefore, must be competent in pain assessment methods in order to identify pain in critically ill patients so that appropriate analgesia can be administered.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

Which one of the following tools can be used to assess pain in critically ill patients who cannot self-report?

Topics

Further your knowledge

References

- Bhattacharyya, A, Laycock, H, Brett, SJ, Beatty, F & Kemp, HI 2023, ‘Health Care Professionals' Experiences of Pain Management in rhe Intensive Care Unit: A Qualitative Study’, Anaesthesia, vol. 79, no. 6, viewed 31 July 2024, https://associationofanaesthetists-publications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/anae.16209

- Chanques, G & Gélinas, C 2022, ‘Monitoring Pain in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU)’, Special Issue Insight, vol. 48, viewed 1 August 2024, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00134-022-06807-w

- Devlin, JW et al. 2018, ‘Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU’, Critical Care Medicine, vol. 46, no. 9, viewed 1 August 2024, https://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal/fulltext/2018/09000/clinical_practice_guidelines_for_the_prevention.29.aspx

- Health.vic 2024, Identifying Pain, Victoria State Government, viewed 1 August 2024, https://www.ausmed.com.au/learn/articles/identifying-pain

- International Association for the Study of Pain 2020, ‘IASP Announces Revised Definition of Pain’, IASP News, 16 July, viewed 31 July 2024, https://www.iasp-pain.org/publications/iasp-news/iasp-announces-revised-definition-of-pain/

- Mallet, J, Albarran, J & Richardson, R 2013, Critical Care Manual of Clinical Procedures and Competencies, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

- MDCalc n.d., Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) for Pain Assessment in Intubated Patients, MDCalc, viewed 1 August 2024, https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3622/behavioral-pain-scale-bps-pain-assessment-intubated-patients

- Nazari, R et al. 2022, ‘Diagnostic Values of the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool and the Behavioral Pain Scale for Pain Assessment among Unconscious Patients: A Comparative Study’, Indian J Crit Care Med., vol. 26, no. 4, viewed 1 August 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9067504/

- Nordness, MF, Hayhurst, CJ & Pandharipande, P 2021, ‘Current Perspectives on the Assessment and Management of Pain in the Intensive Care Unit’, J Pain Res., vol. 14, viewed 1 August 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8214553/

- Pandharipande, P & Hayhurst, CJ 2024, Pain Control in the Critically Ill Adult Patient, UpToDate, viewed 31 July 2024, https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pain-control-in-the-critically-ill-adult-patient

- Seo Y, Lee H, Ha EJ & Ha TS 2022, ‘2021 KSCCM Clinical Practice Guidelines For Pain, Agitation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disturbance in the Intensive Care Unit’, Acute Crit Care., vol. 37, no. 1, viewed 31 July 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8918705/

New

New