At least 200 million people are infected with malaria every year. In 2023, there were 597,000 malaria deaths worldwide (WHO 2024).

What is Malaria?

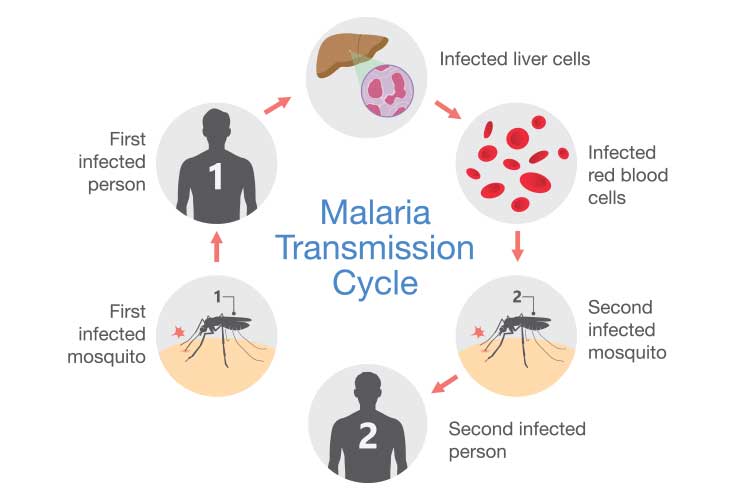

Malaria is an infectious disease caused by the parasite Plasmodium, which is transmitted through the bite of a female Anopheles mosquito. In rare cases, it is transmitted congenitally, via blood transfusion or through shared injecting equipment (WHO 2024; NSW Health 2024).

When female Anopheles mosquitoes feed on blood to nurture their eggs, they can pick up Plasmodium parasites from humans infected with malaria. These mosquitoes will then become vectors (carriers) and transmit Plasmodium to other people they bite (CDC 2024).

Should Australians be Worried About Malaria?

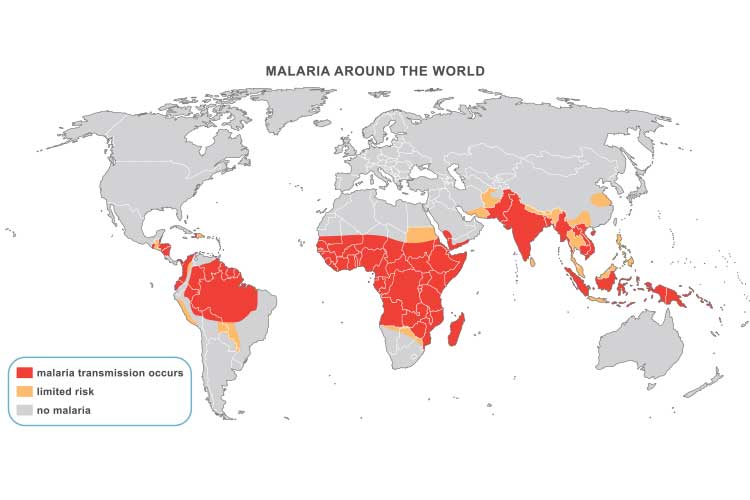

Australia was certified as being malaria-free by the World Health Organisation in 1981 (WHO 2025).

Despite this, there are still reasons to be vigilant:

- Every year, several hundred imported cases from travellers are recorded in Australia.

- Those who travel to areas where malaria occurs are at risk of being infected if they do not take appropriate precautions. Areas of particular risk to Australians include:

- The south-west Pacific (Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu)

- Parts of Asia (particularly parts of Thailand, Myanmar, Sabah, Vietnam and India)

- Parts of Africa (particularly East African countries).

- Local cases are occasionally reported in the Torres Strait in Australian territory.

- The Anopheles mosquito lives in parts of the Northern Territory.

(QLD Health 2022; VIC DoH 2024; NT Health 2023)

If Australia is to remain free of malaria, it is imperative that all cases are diagnosed and treated appropriately. Anyone who has been in an area where malaria has occurred within the previous 12 months and who develops a fever should be checked for malaria, both for their own sake and to prevent malaria from getting into the community.

Types of Plasmodium

There are five main species of Plasmodium that cause malaria in humans. They differ somewhat in areas where they mainly occur, the symptoms they cause, and the treatment required.

- Plasmodium falciparum causes the most serious and life-threatening illness, potentially resulting in liver or kidney failure, convulsions or coma.

- Plasmodium vivax generally causes a less serious illness but can lie dormant in humans for months or years.

- Plasmodium ovale generally causes a less serious illness but can lie dormant in humans for months or years.

- Plasmodium malariae generally causes a less serious illness.

- Plasmodium knowlesi usually only causes malaria in monkeys, but there have been some human cases.

(myDr 2024; Stanford Health Care 2019)

Malaria Symptoms

After being bitten by an infected mosquito, Plasmodium parasites enter the person’s liver, where they begin to multiply. After a number of days (depending on the type of Plasmodium), the parasites re-enter the bloodstream, invade red blood cells and reproduce (WEHI 2024).

The initial flu-like symptoms may include:

- Fever, which may be constant or come and go

- Chills

- Sweating

- Headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Muscle and joint pains

- Confusion

- Reduced appetite

- Diarrhoea

- Abdominal pain

- Coughing

- Anaemia.

(NSW Health 2024; SA Health 2022)

Severe malaria may present as:

- Impaired consciousness or coma

- Prostration (inability to sit up without assistance)

- Convulsions

- Pulmonary oedema

- Shock

- Acidosis

- Hypoglycaemia

- Severe anaemia

- Renal impairment

- Jaundice

- Recurrent or prolonged bleeding (e.g. from nose or gums)

- Hyperparasitaemia.

(Bennett 2024; Zekar & Sharman 2023)

Diagnosing Malaria

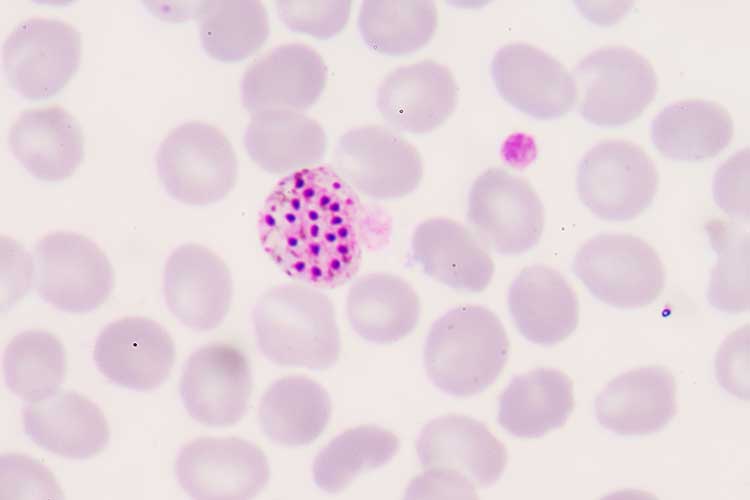

Laboratory diagnosis of malaria is by microscopy. A blood specimen is spread as a smear and examined to confirm the presence of Plasmodium and calculate the percentage of red cells containing the parasites (Queensland Health 2023).

Treating Malaria

Malaria is treated with antimalarial medicines to kill the Plasmodium parasites. The exact medicine will depend on factors such as the species of Plasmodium involved, the severity of symptoms, the age of the patient and pregnancy (Mayo Clinic 2023).

Note that there is increasing resistance to antimalarials, so treatment should be overseen by an infectious disease specialist or expert (SA Health 2022).

Cases of severe malaria require intravenous administration of antimalarials. If the attack is not classified as severe, oral medications may be used (Buck & Finnigan 2023).

P. vivax and P. ovale may have dormant stages (hypnozoites) that persist in the liver and are not killed by the medication used for the acute attack. The patient may need to take primaquine to eradicate these dormant parasites (Buck & Finnigan 2023).

Preventing Malaria

Anyone travelling to a malaria-endemic region should take precautions, including consulting a physician who can prescribe preventative antimalarial drugs (NSW Health 2024).

No antimalarial drug is 100% effective, so taking precautions to avoid mosquito bites is also crucial. These include:

- Being vigilant when spending time outdoors around dawn and dusk, and into the evening

- Wearing loose, light-coloured, long-sleeved shirts and long pants when outdoors

- Wearing socks and covered shoes when outdoors

- Applying mosquito repellent to exposed skin and on clothing

- Avoiding perfumes, colognes or aftershaves, which may attract mosquitoes

- Sleeping in screened or air-conditioned rooms, if possible, and using a mosquito net if not

- Using ‘knockdown’ sprays, mosquito coils and plug-in vaporising devices.

(NSW Health 2024; Better Health Channel 2024)

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

True or false: Some Plasmodium parasites can stay dormant in the body for an extended period of time.

Topics

References

- Bennett, WN 2024, Malaria, Medscape, viewed 2 June 2025, https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/221134-overview

- Better Health Channel 2024, Malaria, Victoria State Government, viewed 2 June 2025, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/malaria

- Buck, E & Finnigan, NA 2023, ‘Malaria’, StatPearls, viewed 2 June 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551711/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2024, About Malaria, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, viewed 30 May 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/index.html

- Mayo Clinic 2023, Malaria, Mayo Clinic, viewed 2 June 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/malaria/symptoms-causes/syc-20351184

- myDr 2024, Malaria Overview, Tonic Digital Media, viewed 2 June 2025, https://mydr.com.au/travel-health/malaria-overview/

- NSW Health 2024, Malaria Fact Sheet, New South Wales Government, viewed 30 May 2025, https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/factsheets/Pages/malaria.aspx

- NT Health 2023, Malaria, Northern Territory Government, viewed 30 May 2025, https://health.nt.gov.au/public-health-notifiable-diseases/malaria

- Queensland Health 2022, Communicable Disease Control Guidance: Malaria, Queensland Government, viewed 30 May 2025, https://www.health.qld.gov.au/disease-control/conditions/malaria

- Queensland Health 2023, Malaria: Queensland Health Guidelines for Public Health Units, Queensland Government, viewed 2 June 2025, https://www.health.qld.gov.au/cdcg/index/malaria

- SA Health 2022, Malaria - Including Symptoms, Treatment and Prevention, Government of South Australia, viewed 2 June 2025, https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/conditions/infectious+diseases/malaria/malaria+-+including+symptoms+treatment+and+prevention

- Stanford Health Care 2019, Types of Malaria Parasites, Stanford Medicine, viewed 2 June 2025, https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-conditions/primary-care/malaria/types.html

- Victoria Department of Health 2024, Malaria, Victoria State Government, viewed 30 May 2025, https://www.health.vic.gov.au/infectious-diseases/malaria

- The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research 2024, Malaria, WEHI, viewed 2 June 2025, https://www.wehi.edu.au/research-diseases/immune-health-and-infection/malaria

- World Health Organisation 2024, Malaria, WHO, viewed 30 May 2025, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria

- World Health Organisation 2025, Countries and Territories Certified Malaria-free by WHO, WHO, viewed 30 May 2025, https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/elimination/countries-and-territories-certified-malaria-free-by-who

- Zekar, L & Sharman, T 2023, ‘Plasmodium falciparum Malaria’, StatPearls, viewed 2 June 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555962/

New

New