Choking is the second most common cause of preventable death in residential aged care (Ibrahim et al. 2015).

Knowing how to prevent choking and correctly perform first aid for this life-threatening emergency is an essential skill.

Note that the first aid procedure detailed in this article should be used for adults only.

What is Choking?

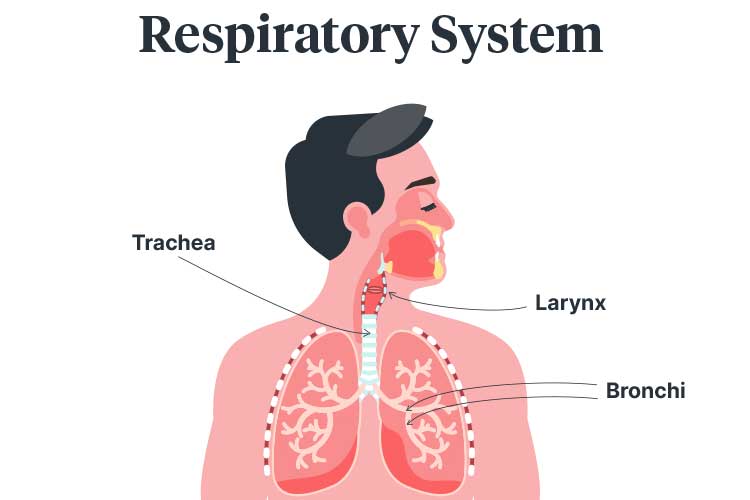

The trachea (windpipe) is a tube-like structure in the respiratory system enabling the passage of air from the larynx to the bronchi and finally to the lungs (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2024).

Choking occurs when the trachea is completely or partially blocked by a foreign body (food, liquid or another object), obstructing airflow (Queensland Government 2019; Gonzalez & Kahn 2019).

Choking can be gradual or sudden, and it may only take a few seconds for the airway to become completely blocked. The specific symptoms experienced by a choking person will depend on the foreign body causing the obstruction and the severity of the blockage (ANZCOR 2024).

If airflow is completely blocked, the brain will be deprived of oxygen. It only takes four minutes without oxygen for brain damage to occur (Headway 2018).

A person who is choking may be conscious or unconscious. Conscious patients and unconscious patients must be managed differently (ANZCOR 2024).

Older Adults and Choking

While choking is a prevalent cause of injury-related death in infants (Queensland Government 2019), did you know that older adults over the age of 65 are seven times more likely to choke on food than children aged 1 to 4 (Cichero 2018)?

Loss of muscle mass and strength - which is a natural part of the ageing process - affects muscles related to chewing and swallowing, increasing the risk of choking (Cichero 2018). Dysphagia (swallowing difficulty) is also common among older adults (Healthdirect 2022).

Pathological factors such as dementia, stroke, functional decline, and medicines may further increase the risk (Health.vic 2023).

Read: Dysphagia and Swallowing

Choking Under the Strengthened Aged Care Quality Standards

Standard 5: Clinical Care - Outcome 5.5: Clinical Safety (Action 5.5.2) under the strengthened Aged Care Quality Standards requires aged care organisations to establish processes for ensuring safe chewing and swallowing during:

- Eating

- Drinking

- Talking

- Oral medication administration

- Oral care.

(ACQSC 2024)

Common Causes of Choking

- Eating or drinking too quickly

- Swallowing food before chewing it properly

- Swallowing small bones or other objects

- Inhaling small objects

(Queensland Government 2019)

Choking Risk Assessment

It is important to identify residents who may be at risk of choking. These may include:

- Residents with swallowing disorders

- Residents who have choked before

- Residents who display impulsive behaviours (as they may be more likely to put things in their mouth or stand up suddenly)

(Health.vic 2023)

Residents with an established risk of choking should be referred to an appropriate specialist, such as a speech pathologist, dietitian or dentist. It is important that the results of a risk assessment, and any subsequent recommendations that have been made, are appropriately recorded, communicated and put into practice (Health.vic 2023).

Signs of Choking

If the resident is conscious, they may show some of the following signs:

- Extreme anxiety

- Agitation

- Panic or distress

- Gasping

- Coughing

- Loss of voice

- Universal choking sign (clutching the neck with thumb and fingers)

- Neck or throat pain

- Difficulty speaking, breathing or swallowing

- Gagging

- Wheezing or abnormal breathing noises

- Colour changes in face (e.g. blue lips or red face)

- Chest pain

- Collapse

- Watery eyes

(ANZCOR 2024; Queensland Government 2019; Better Health Channel 2014)

If there is partial airway obstruction, the resident will still be able to breathe, speak and cough to some extent (Better Health Channel 2014). Other indications of partial obstruction include:

- Laboured breathing

- Noisy breathing

- Abnormal breathing

- Being able to feel some escape of air from the resident/patient’s mouth

(ANZCOR 2024; Better Health Channel 2014)

Indications for complete airway obstruction include:

- Increased work of breathing

- Vigorous attempts at breathing

- No sound of breathing

- No escape of air from the nose or mouth

- Cyanosis (turning pale, then blue)

- Inability to breathe, speak or cough

- Altered state of consciousness

(ANZCOR 2024; Better Health Channel 2014)

Note that airway obstruction in a resident who is unresponsive and non-breathing may not be apparent until rescue breathing has commenced (ANZCOR 2024).

How to Perform First Aid for Choking

(Adapted from ANZCOR 2024; Health.vic 2023)

If the resident is conscious, remember to tell them what you are doing and why.

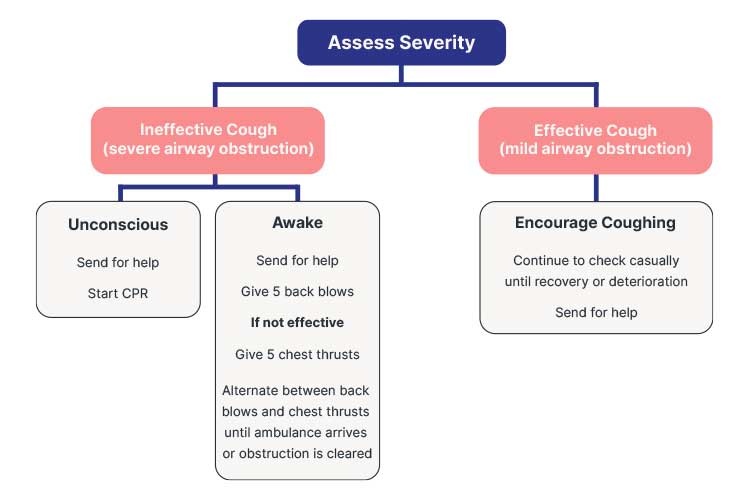

The first step in managing choking is to assess the severity of the airway obstruction. This can be done by determining whether the resident/patient is able to cough effectively (ANZCOR 2024).

Effective Cough (Awake Resident/Patient)

If the resident is able to effectively cough, this indicates a mild airway obstruction. You should:

- Reassure the resident and encourage them to keep coughing. They may be able to expel the object on their own.

- If the object does not dislodge, call an ambulance.

(ANZCOR 2024)

Ineffective Cough (Awake Resident/Patient)

An ineffective cough indicates a severe airway obstruction (ANZCOR 2024).

First aid for severe airway obstruction in a conscious resident/patient requires the use of two techniques: back blows and chest thrusts.

Back Blow

In order to perform a back blow, keep the resident standing unless they are already seated. Bend the resident forward, and using the heel of your hand, give a sharp blow to their back between their shoulder blades (Healthdirect 2023). Back blows aim to completely or partially dislodge, or loosen, the foreign object by creating an increase in pressure in the obstructed airway. If the foreign object is loosened, the resident may be able to cough (British Red Cross 2018).

Chest Thrust

When delivering a chest thrust, place one hand on the middle of the resident’s back for support. Using the heel of your hand, give a short, sharp upward thrust to the resident’s lower sternum. Chest thrusts should be performed sharper and at a slower rate than CPR compressions (St John Ambulance Australia 2022).

Note: The use of abdominal thrusts (aka the Heimlich manoeuvre) is no longer recommended due to evidence of life-threatening complications (ANZCOR 2024).

The procedure for a conscious patient with an ineffective cough is to:

- Call an ambulance.

- Deliver five back blows. Check to see if the object has been dislodged after each blow. The aim is not to deliver all five blows but to dislodge the object.

- If the object has not been dislodged after five back blows, perform five chest thrusts. Check to see if the object has been dislodged after each thrust. The aim is not to deliver all five thrusts but to dislodge the object.

- If the object has not been dislodged after five chest thrusts, continue alternating between five back blows and five chest thrusts as long as the resident/patient is still responsive.

(Health.vic 2023)

Unconscious Resident/Patient

If the resident/patient becomes unresponsive:

- Perform a finger sweep if the foreign object is visible in the airway.

- Call an ambulance.

- Start CPR.

(Health.vic 2023; ANZCOR 2024)

Read: Adult Basic Life Support (BLS) Using DRSABCD

Care Process Following a Choking Incident

After a choking incident has occurred:

- Ensure the resident is safe and being closely monitored following the event. It’s important to discuss the event and provide reassurance.

- Notify the resident's general practitioner and family about the event.

- Determine the probable cause of the choking incident and ensure you are aware of dysphagia signs and symptoms.

- Refer the resident to a speech pathologist for a swallowing assessment and recommendations if appropriate.

- Assess whether the resident/patient’s food and fluid intake are appropriate (if the resident/patient is on a modified diet or fluids), and refer them to a dietitian if necessary.

- Put into practice an individualized risk reduction and prevention plan.

- Review the resident’s medicines and identify any medicines that affect swallowing or saliva.

- Ensure that any new changes, risks, plans, and requirements are communicated across the care team.

- Make any necessary referrals.

- Monitor the resident and perform a choking risk assessment at least every six months or after the resident has had a change in their condition.

- Ensure the resident is appropriately educated on choking risk factors and safe swallowing techniques.

- Ensure staff are appropriately educated on choking risk factors, recognition, management, and interventions.

(Health.vic 2023)

Choking Prevention Strategies

For residents who have been identified at risk of choking:

- Ensure ‘at-risk’ residents/patients are appropriately identified and supervised.

- Ensure the right foods are given to the right residents (as some residents might have a modified textured diet).

- When providing assistance with meals, you may consider:

- Encouraging the resident to cough after swallowing

- Giving the resident adequate time to chew and swallow

- Ensuring the resident has swallowed before giving them more food or drink

- Alternating mouthfuls of food with mouthfuls of fluid

- Checking the resident’s mouth for residual food after each meal.

- When the resident is eating, ensure they are sitting upright with their chin tucked or turned.

- Consider swallowing manoeuvres (e.g. supraglottic and super supraglottic swallow, effortful swallow, Mendelsohn manoeuvre).

- Consider feeding aids (e.g. adapted cups, shallow spoons, non-slip table mats, angled utensils).

- Reduce environmental distractions while the resident/patient is eating.

- Assist the resident/patient with oral hygiene before and after each meal.

For further information on meal assistance, read: Meal Assistance in Aged Care.

(Health.vic 2023)

Note that this is a written refresher on choking first aid and is not designed to be a substitute for comprehensive education and hands-on training. Always follow your organisation's policies and procedures.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

What is the first step in aiding a conscious resident who is choking and can cough effectively?

Topics

Further your knowledge

Free

Free Free

Free Free

Free

References

- Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission 2024, Standard 5: Clinical Care, Australian Government, viewed 21 June 2024, https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/strengthened-aged-care-quality-standards-august-2025?language=en

- Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation 2024, Guideline 4 – Airway, ANZCOR, viewed 26 January 2024, https://www.anzcor.org/home/basic-life-support/guideline-4-airway/

- Better Health Channel 2014, Choking, Victoria State Government, viewed 29 January 2024, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/ConditionsAndTreatments/choking

- British Red Cross 2018, Learn First Aid for Someone Who is Choking, British Red Cross, viewed 29 January 2024, https://www.redcross.org.uk/first-aid/learn-first-aid/choking

- Cichero, JAY 2018, ‘Age-Related Changes to Eating and Swallowing Impact Frailty: Aspiration, Choking Risk, Modified Food Texture and Autonomy of Choice’, Geriatrics (Basel), vol. 3, no. 4, viewed 26 January 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6371116/#B34-geriatrics-03-00069

- Encyclopaedia Britannica 2024, ‘Trachea’, Encyclopaedia Britannica, viewed 26 January 2024, https://www.britannica.com/science/vocalization

- Headway 2018, Hypoxic Brain Injury, Headway, viewed 26 January 2024, https://www.headway.org.uk/about-brain-injury/individuals/types-of-brain-injury/hypoxic-and-anoxic-brain-injury/

- Healthdirect 2023, Choking, Australian Government, viewed 29 January 2024, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/choking

- Healthdirect 2022, Dysphagia (Difficulty Swallowing), Australian Government, viewed 26 January 2024, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/dysphagia

- Health.vic 2023, Choking Standardised Care Process, Victoria State Government, viewed 26 January 2024, https://www.latrobe.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/1152432/SCP-Choking.pdf

- Ibrahim, JE, Murphy, BJ, Bugeja, L & Ranson, D 2015, ‘Nature and Extent of External-Cause Deaths of Nursing Home Residents in Victoria, Australia’, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 63, no. 5, viewed 26 January 2024, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25940003/

- Gonzalez, A & Kahn, A 2019, ‘What You Should Know About Choking’, Healthline, 4 September, viewed 26 January 2024, https://www.healthline.com/health/choking-adult-or-child-over-1-year

- Queensland Government 2019, Choking, Queensland Government, viewed 26 January 2024, http://conditions.health.qld.gov.au/HealthCondition/condition/1/87/257/Choking

- St John Ambulance Australia 2022, First Aid Fact Sheet: Choking Adult or Child (Over 1 Year), St John Ambulance Australia, viewed 29 January 2024, https://stjohn.org.au/assets/uploads/fact%20sheets/english/Fact%20sheets_choking%20adult.pdf

New

New