Healthcare Management

A guide to practice for nurses, midwives and healthcare professionals.

36mPublished: 04 March 2020

36mPublished: 04 March 2020

In addition to managing resources and budgets, being an advocate for and developing staff (Rogers 2005) is a key managerial responsibility. Managing people successfully - facilitating and coordinating their work rather than directing and controlling - requires great skill and certain personal qualities as outlined below.

Qualities and Abilities for Effective Management

An effective manager has personal qualities that allow them to be a role model, a mentor and a leader. Qualities and abilities required to be an effective healthcare or nurse manager include:

- Credibility;

- Self-belief;

- Leadership;

- Ability to inspire trust and respect; and

- Ability to empower.

A Healthcare Manager's Core Responsibilities

The key to being an effective manager lies in providing nursing staff with a balance of adequate resources and support to deliver quality patient care, as well as empower their team to develop and grow as individuals.

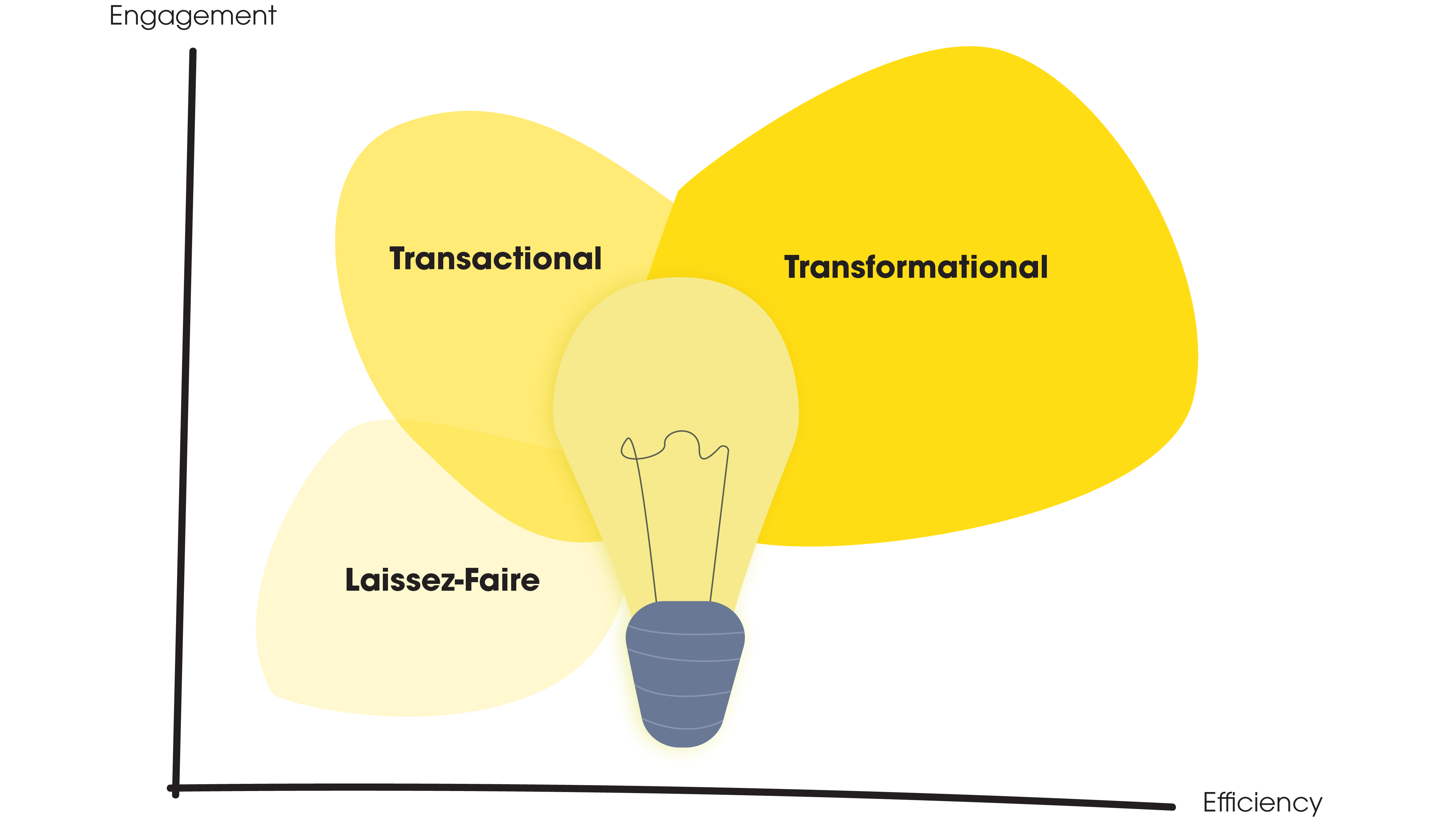

Leadership Styles

From all models of leadership theory, two major leadership styles remain most prominent:

- Transactional leadership and

- Transformational leadership.

Transactional Leadership

Transactional leadership is a functional, production-centred approach that reviews the needs of the group, the task and the individual (Sellgren et al. 2006). This model focuses on the function of leadership in achieving a task, taking into account the needs of individuals and the needs of the group (Adair 1983).

The components of this model include (Henderson, Phillips & Lewis 2000):

- Planning: drawing together all the information required;

- Initiating: getting together with the team and sharing the task;

- Controlling: measuring what is happening and where the team is up to; and

- Supporting: providing the motivation where required.

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership is a humanistic approach that involves a combination of charisma, belief, style, flexibility and authenticity (Ward 2002). This focuses on the relationship of the leader with team members, especially the leader’s ability to provide inspiration.

The components of the transformational leadership model include (Riggio 2009):

- Idealised influence: the leader role models;

- Inspirational motivation: inspires and motivates the vision, displays charisma;

- Individualised consideration: demonstrates genuine concern for the needs and feelings of others;

- Intellectual stimulation: challenges staff to be innovative and creative.

What Kind of Leader Should You Be?

Transformational leadership is the preferred style in the caring professions in which the emphasis is on relationships with people.

In this regard, the following aspects of transformational leadership are especially significant:

Having an ability to tap into individual resources

Being able to rise above and review situations (the so-called 'helicopter' trait).

Working across boundaries and disciplines.

Bringing vitality, belief and inspiration

Being confident self-assured and courageous.

Motivating and enthusing people to embrace this vision.

Being charismatic, respected and having integrity

Exuding professionalism while remaining approachable.

Empowering, enabling and involving the team.

Showing concern for people in terms of their personal and professional needs.

Creating and expressing an exciting vision for a team

Showing creativity, ingenuity and innovation.

Sharing power and empowering others.

The above traits are not necessarily innate; people can develop them through lifelong learning. Employers have a responsibility to provide personal and professional development for their employees, and most organisations offer these opportunities.

Leadership courses are essential in developing current and future managers (Fister-Gale 2002), and all staff, regardless of position and status, should be given opportunities to lead, particularly if they are already demonstrating their potential and desire to lead.

Motivation

Motivation is what makes us want to do our job. One study concluded that healthcare professionals tend to be motivated more by intrinsic factors, implying that this should be a target for effective employee motivation.

This is how partcipiants of the study ranked the following four motivators, in order of importance to them (Lambrou et al. 2010):

Maslow’s Theory of Motivation

A relevant theory on motivation for the nurse manager to be familiar with is that of Maslow’s (1970).

Maslow's theory of motivation proposes that humans are motivated by a ‘hierarchy of needs’, which are divided into physiological and psychological needs. It is only once the physiological or basic human needs are satisfied that an individual’s focus can then move on to satisfying psychological or ‘higher’ needs. When a need is met, it no longer motivates and is replaced by the next highest need.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs:

- Physiological needs: hunger, thirst, bodily comfort;

- Safety needs: safety and security;

- Relationship needs: love, affection, sense of belonging;

- Needs for esteem: self-esteem, confidence, respect; and

- Self-actualisation: a desire to reach one’s full potential.

In the healthcare workplace, these higher needs might involve being excellent in a specific job, achieving high academic standards or reaching a certain positional status.

Work involves a significant proportion of a person’s life, and it is in the best interests of both staff and an organisation to provide a supportive environment in which needs can be fulfilled.

Recruitment Process

- Review requirements for the position;

- Review job description and person specification;

- Advertise the position;

- Establish the selection panel and process;

- Shortlist the candidates;

- Conduct the interview and assessments;

- Check references;

- Make the decision;

- Nominate successful applicants;

- Write the selection report;

- Inform the candidates;

- Sign contracts of employment; and

- Induct the successful candidate.

General Template for a Job or Position Description

Organisational Heading

The organisation states its name and location. This can include the organisation’s logo.

Job or position description

(i) Title

This describes the role that the person will be required to fill. The title can be worded carefully to reflect the nature of the position; e.g. ‘quality coordinator’.

(ii) Award classification

This relates the position to relevant award classification; e.g. registered nurse.

Terms and conditions of employment

This might be stated simply as being ‘per the relevant award’ (with the name of the award being stated).

Department (or section)

This confirms the physical area in which the employee is required to work; e.g. oncology ward.

Responsible to

This reflects the line of authority as detailed in the organisation chart; e.g. director of nursing.

Hours per week

This states the number of hours that the person is contracted to work. Alternatively, this can be set out in the employment contract.

Performance appraisal

If a statement of the appraisal arrangements is included, initial appraisal should be conducted three months after commencement date, and then annually using the position description and agreed performance objectives.

Purpose of the position

This might include a statement that binds the position to the philosophy and objectives of the organisation; e.g.

‘This registered nurse position is a fundamental part of a management system that is designed to ensure the professional and responsible management of nursing-service delivery in a manner that is consistent with philosophy, objectives, and policies of the organisation.’

Such a statement is useful in providing a framework for understanding why the position has been constructed.

Body of the description

The formulation of the position description should be based upon the philosophy and objectives of the organisation.

There is no right or wrong way of writing the body of a job or position description. One approach is to divide the description into two major columns. The left hand column lists major performance standards and the right column provides specific key performance indicators of each performance standard.

Extra information

Management may wish to provide supplementary information. This can be included as an attachment to the position description, or it can be included in the orientation manual. The extra information elaborates on the role as part of the broader management framework. In its simplest form this might simply state:

- That the job or position description forms a part of the recruitment selections and appraisal process,

- That it is routinely updated and

- That staff members are required to sign two copies of the description (which each party retaining a copy for further reference).

What is a Policy?

Policies are strategic operational decisions about what is to be achieved, how it is to be achieved, how resources are used, how organisations manage adverse events and how they ensure that negative events don’t happen again. They are decisions that affect large numbers of cases rather than single events, and they represent the way the organisation wishes to be viewed by people from the outside.

What is a Procedure?

Procedures are the specific ways of doing things that ensure policies are met. For example: a policy states that it is the responsibility of the clinical nurse specialist to order after-hours medications. Accompanying the policy is a procedure detailing precisely how to obtain medication after hours, including pathways to be followed if the usual sources are available.

Example / Template Policy

Introduction

The introduction (or preamble) is a statement of what the policy is all about - in the simplest possible terms. There is no need to be too specific at this point, the aim of this section is to inform the reader as to whether this is the policy they are looking for, or to keep looking through the collection.

Policy

The policy is the main statement setting out what is required and how the organisation plans to do it. Decisions are made as to how specific the statement should be, and if outcome measures are to be included to determine whether the policy is working effectively, and how staff implement it.

Statement of responsibility

A statement of responsibility defines to whom the policy applies. Does it apply to all staff members or only nurses? Does it apply to all sections within the department or only one section; e.g. a community service attached to an in-patient facility? A general principle is that policies, when appropriate, should apply to as many people in the organisation as possible.

Authority

Policies cannot be written and adopted by anybody; they need to be authorised by the appropriate person or committee. Usually, voices are authorised by management. The chairperson of the board, who might not be legally accountable for such decisions, delegates authority to the chief executive officer.

Depending on the organisational structure (which in itself is another policy), policy authorisation might be delegatee to a committee or a particular person in a division or department. In these cases, it would only hold authority in that division of the organisation.

Dates of application and review

Over time, an organisation is likely to generate several ‘generations’ of policies and there must be some way of knowing which document is currently in force. For that reason, and because it is simply good practice to date documents, the date of authorisation and review must be stated.

Policies are living documents, constantly evolving to adapt to the conditions that affect organisations and frequently reviewed to ensure they reflect the current realities in health services.

References

Unlike academic publications, references in policy documents point not only to where material was derived but also to other sources that support the policy. For example, a medication policy might contain cross-references to the nursing board regulations, state government Acts that control medication administration, professional organisation statements on medication, National Mental Health Standards, accreditation standards and other policies and procedures within an organisation’s own framework. These references increase the authority of the policy.

Policy Document Format

A standardised format should be adopted organisation-wide. Some guidelines for a policy document format:

- Set up a blank/template file of the approved standardised style, including font style, font size, indents, margins, gutters and alignment rules.

- Define a ‘house style’ in respect to written conventions, spelling, formatting etc.; e.g. which dictionary to follow and the tone of expression (usually formal).

- Insert page numbers automatically.

- Include the author’s name, the file name, the pathway and set out all the above-required sections.

Planning a Meeting

When planning a meeting some factors to consider might include: where, and at what time, should the meeting be held? What are the desired outcomes? Will audiovisual equipment be used? How many breaks will be needed? What kind of seating will be needed?

Once the objectives are defined, it is easier to develop an agenda. The manager should make the purpose of the meeting clear. Be specific about the outcome you want from each agenda item (Davey 2017).

Consider the following points when planning a meeting:

- Schedule important topics (those that will be most critical to the achievement of expected objectives) towards the beginning of the meeting;

- Separate the difficult topics;

- Evaluate realistically the number of topics that can be covered in the established time for the meeting;

- State (in the agenda) the date, time, place and purpose of the meeting, the items for discussion and the time allocated for discussion of each item;

- Remember that participants will not mind finishing a meeting early, but meetings that run over the expected time frustrate many people;

- Circulate the draft agenda to the invited participants and request their input;

- Incorporate any suggestions of those attending into another draft of the agenda and recirculate the final version;

- Ensure that all materials required for effective discussion are distributed before the meeting so that participants have time to prepare for knowledge-based discussion and decision-making; and

- Ensure that participants are aware they are expected to review the material and to notify the chair if they are unable to attend.

Example Meeting Agenda

23 June, 9:30 AM

Blue Room, Star Hotel

1 |

9:30 |

Call to order; establish quorum |

|---|---|---|

2 |

9:35 |

Minutes |

3 |

9:40 |

Financial |

4 |

9:50 |

Reports from committees |

5 |

10:10 |

Correspondence |

6 |

10:15 |

Break |

7 |

10:25 |

Unfinished business

|

8 |

10:45 |

Other business |

9 |

10:55 |

Review meeting |

10 |

11:00 |

Adjournment |

High-Quality Patient Outcomes

Patient outcomes are directly impacted by how staff experience their work (Nursing Times 2014). The level of engagement, empowerment and stress levels of staff can all have an effect on the patient. One tool at a manager’s disposal to directly improve staff experience is the roster. In order to achieve quality-patient outcomes and staff experience, the roster must provide the following three things.

1. Adequate Clinical Hours

Adequate nursing intensity, or patient acuity, can be measured by using a patient-nurse dependency system to estimate the level of nursing intensity required when designing roster patterns. To do this, it is necessary to have access to historic patient-acuity trends to provide data for the most accurate predictions.

2. Manage Peak-Activity Periods

Regular patient-care activity trends generate increased workload at specific times within a shift. Examples include admission and discharge periods, scheduled elective surgery, patient-transfer periods, routine patient-care activities, doctors rounds and routine patient-care programs, clinics or services conducted.

3. Appropriate Staff Skill Mix

To match clinical work requirements to nursing staff skills, it is essential that the particular skill levels of each nurse are evaluated and identified. Nursing skill levels may be defined as team leaders (able to be in charge on a shift), competent (requires no direct supervision), advanced beginner (requires guidance in complex situations); and novice (new practitioner requiring some supervision and guidance).

Watch: The Business of Caring

Staff Satisfaction

More flexible rosters can be achieved by:

- Maintaining a mix of permanent full-time and permanent part-time staff;

- Rostering 4-hour shifts to permanent part-time staff (extended if necessary);

- Utilising a range of long (10-12-hour) shifts in combination with short (8, 6 and 4-hour) shifts;

- Establishing a pool roster where permanent full-time and part-time staff are rostered shifts but are not attached to any ward, being placed on a shift-by-shift basis;

- Retaining a group of casual employees;

- Establishing working relationships with nursing agencies;

- Developing systems that accomodate roster request and shift changes after roster development; and

- Establishing systems such as time off in lieu, banked hours and flex-time.

Cost Effectiveness

Managers are often presented with a budget target that they may not have been involved in developing. This target is usually presented as a financial figure, or as a certain number of labour hours; that is, a number of hours per patient per day (HPPD).

Using retrospective acuity data, a roster profile can be created. To establish the average daily HPPD from a roster profile, take the following steps:

Calculating Hours Per Patient Per Day (HPPD)

Step

Example

1. Total the average number of full-time equivalent (FTE) shifts rostered for each shift of the week (A) shifts.

87.5 FTE

2. Calculate the average hours per week (A x 8) hours.

700 hours

3. Calculate the average hours per day (B) by dividing the weekly number (obtained in Step 2) by 7.

100 hours

4. Calculate the average number of patients per day (C).

26 Patients

5. Calculate the average number of hours per patient per day by dividing B by C. This gives the HPPD.

3.85 HPPD

6. Allow for casual or agency hours (for example, 10%) for sick leave and unpredictable peaks in workloads.

0.38 HPPD

7. Calculate total HPPD by adding the number obtained at Step5 to the number obtained at Step 6.

4.23 HPPD

(3.85 + 0.38)

Cost Calculation of Rostered Clinical Hours

Average total HPPD:

3.8 HPPD

Total Cost for permanent staff/day ( @ $36/hr):

$3,600

Total for one month roster (30 days):

$108,000

Total for additional 10% casual hours (@ $46/hr):

$13,634

Total monthly cost of clinical rostered hours:

$121,634

Conducting Performance Reviews

A performance appraisal is an important and official opportunity for both manager and staff member to communicate freely, and it is important to treat it as such.

Make sure you choose a quiet room to hold the apprasal, somewhere with no interruptions. Turn off pagers, put mobile phones on silent, ensure your conversations are not overheard and allow enough time to go through the process.

Initial

Appointment to position

Orientation

Percepting/mentoring

12 Months

Individual performance review

Assessment and evaluation

Feedback and rewards

Agree on supports and training requirement

Implement and monitor agreed performance plan

6 Months

Discuss and appraise performance so far

Set and agree on goals and learning needs in a performance plan

12 Months After

Another individual performance review

Key Steps in a Performance Review

- Prepare and agree on a time and place;

- Gather thoughts, information, evidence and feedback;

- Complete documentation before meeting;

- Put the person at ease an ensure confidentiality;

- Remain clear and objective;

- Follow a plan or process;

- Allow enough time;

- Document the discussion and agreed outcomes; and

- Sign the record and keep copies for further reviews.

Giving Effective Feedback

Feedback should be:

- Given at appropriate times.

- Specific, factual and objective.

- Supportive and non-judgmental.

- Outcome-based.

Feedback should not be:

- A one-way conversation.

- General, emotional and subjective.

- Focused personality, character or beliefs.

- Judgmental, threatening or intimidating.

Conducting Difficult Performance Reviews

Effective strategies when conducting difficult performance reviews:

- Listen to any perceived problems;

- Provide helpful feedback and guidance;

- Avoid conflict and disputes;

- Provide support to address learning needs and skill acquisition;

- Reward, coach and support;

- Discuss career expectations;

- Empower staff to suggest solutions and innovations; and

- Provide opportunities for second opinions or referral to human resource personnel.

Poor Performance and PR Disagreements

When poor performances, grievances or disagreements following a PR occur, do not ignore these problems. When addressing poor performance, nurse managers should:

- Be honest about the problem, discussit fairly and listen to what the nurse has to say;

- Review the original performance plan to ensure that it was clear, understood, realistic and achievable;

- Discuss the position and role again, paying attention to role clarity;

- Set and agree on a new plan - with a short timeframe for further discussion; and

- Follow-up on the agreed plan.

- Adair, J 1983, Effective Leadership, Gower, London.

- Croll, N 2008, ‘Chapter 13: Writing Policies and Procedures’, in A Crowther (ed.), Nurse Managers a Guide to Practice, 2nd edn, pp. 145-154, Ausmed, Melbourne.

- Davey, L 2017, ‘The Right Way to Start a Meeting’, Harvard Business Review, 2 March, viewed 26 November 2019, https://hbr.org/2017/03/the-right-way-to-start-a-meeting.

- Falcone, P 2002, ‘Motivating Staff Without Money’, HR Magazine, 1 August, pp. 105-8, viewed 26 November 2019, https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/pages/0802tools.aspx.

- Fister-Gale, S 2002, ‘Building Leaders at All Levels’, Workforce, October, pp. 82-5, viewed 26 November 2019, https://www.workforce.com/2002/10/17/buidling-leaders-at-all-levels/.

- Gadd, M 2008, ‘Chapter 2: Working Relationships and Promotion’, in A Crowther (ed.), Nurse Managers a Guide to Practice, 2nd edn, pp. 7-16, Ausmed, Melbourne.

- Harrison, B 2004, ‘Promotion and Professional Relationships’, in A Crowther (ed.), Nurse Managers a Guide to Practice, 1st edn, pp 11-22, Ausmed, Melbourne.

- Henderson, E, Phillips, K & Lewis, P 2000, Management in Health and Social Care: Understanding People, Module 2, The Open University, Milton Keyes.

- Kramer, M, Maguire, P, Schmalenberg, C, Brewer, B, Burke, R, Chmielewski, L, Cox, K, Krugman, M, Meeks-Sjostrom, D & Waldo, M 2007, ‘Nurse Manager Support: What is It? Structures and Practices that Promote it’, Nursing Administration Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 4, pp, 325-40, viewed 26 November 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17909432.

- Lambrou, P, Kontodimopoulos, N & Niakas, D 2010, ‘Motivation and Job Satisfaction Among Medical and Nursing Staff in a Cyprus Public General Hospital’, Human Resources for Health, vol. 8, no. 26, viewed 26 November 2019, https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1478-4491-8-26.

- Lowe, C 2008, ‘Chapter 16: Rostering’, in A Crowther (ed.), Nurse Managers a Guide to Practice, 2nd edn, pp. 181-202, Ausmed, Melbourne.

- Maslow, AH 1970, Motivation and Personality, Harper & Row, New York, viewed 26 November 2019, http://s-f-walker.org.uk/pubsebooks/pdfs/Motivation_and_Personality-Maslow.pdf.

- Morrison, A, Beckmann, U, Durie, M, Carless, R & Gillies, D 2001, ‘The effects of nursing staff inexperience (NSI), on the occurrence of adverse patient experience in ICUs’, Australian Critical Care, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 116-21, viewed 26 November 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11899636.

- Mulcahy, C 2008, ‘Chapter 8: Dealing with Unhelpful Behaviour’, in A Crowther (ed.), Nurse Managers a Guide to Practice, 2nd edn, pp. 79-88, Ausmed, Melbourne.

- Musker, M 2008, ‘Chapter 4: Leading, Motivating and Enthusing’, in A Crowther (ed.), Nurse Managers a Guide to Practice, 2nd edn, pp. 33-44, Ausmed, Melbourne.

- Nichols, G 1998, ‘How to Improve the quality of the meeting process’, Association Management, January, no. 74.

- Nursing Times Contributor 2014, ‘How Patient and Staff Experiences Affect Outcomes’, 21 November, viewed 26 November 2019, https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/nurse-managers/how-patient-and-staff-experiences-affect-outcomes-21-11-2014/.

- Riggio, RE 2009, ‘Are You a Transformational Leader?’, Psychology Today, 24 March, viewed 26 November 2019, https://www.psychologytoday.com/au/blog/cutting-edge-leadership/200903/are-you-transformational-leader.

- Rogers, L 2005 ‘Why Trust Matters: the Nurse Manager- Staff Nurse Relationship’, Journal of Nursing Administration, vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 421-3, viewed 26 November 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16220053.

- Scarborough, A 2008, ‘Chapter 15: Recruiting and Retaining Staff’, in A Crowther (ed.), Nurse Managers a Guide to Practice, 2nd edn, pp. 33-44, Ausmed, Melbourne.

- Sellgren, S, Ekvall, G & Tomson, G 2006, ‘Leadership styles in nursing management: preferred and perceived’, Journal of Nursing Management, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 348-55, viewed 26 November 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16787469.

- Sheila, A 2008, ‘Chapter 6: Making Meetings Work’, in A Crowther (ed.), Nurse Managers a Guide to Practice, 2nd edn, pp. 55-66, Ausmed, Melbourne.

- Ward, K 2002, ‘A vision for tomorrow: transformational nursing leaders.’, Nursing Outlook, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 121-6, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12085026.

New

New